Translate this page into:

Babesiosis unmasked in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A case report

*Corresponding author: Zeni Kharel, Department of Hematology/Oncology, Rochester General Hospital, Rochester, United States. zeni.kharel@rochesterregional.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kharel H, Kharel Z, Phatak PD. Babesiosis unmasked in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A case report. Indian J Med Sci. doi: 10.25259/IJMS_108_2024

Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)-related autoimmune cytopenias are common. Herein, we present the case of a patient with bicytopenia (anemia and thrombocytopenia), weakly positive direct Coombs test, and increased hemolytic markers. Cytopenias were initially presumed to be autoimmune and related to CLL. He was started on prednisone but to no effect. This prompted re-evaluation of peripheral blood smear which showed intra-erythrocytic inclusions. Considering the patient’s recent extensive hiking in tick-endemic areas and current residence in New York State, polymerase chain reaction for Babesia was performed, yielding a positive result. Treatment with atovaquone and azithromycin for 6 weeks resulted in a significant improvement in both cytopenias and hemolytic markers.

Keywords

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Babesiosis

Autoimmune

Steroids

Case report

INTRODUCTION

Our patient was initially diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)-related autoimmune cytopenias and was treated with steroids but showed no improvement. Further, evaluation revealed intra-erythrocytic inclusions and a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Babesia. Treatment with atovaquone and azithromycin for 6 weeks improved cytopenias and hemolytic markers.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old male with medical history of CLL presented to his primary care physician with complaints of cough, fatigue, low-grade fever, and night sweats for 4 weeks. CLL was diagnosed approximately 14 years ago. He did not have lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias, or rapidly worsening lymphocytosis warranting treatment before this presentation.

Physical examination was unremarkable without palpable lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or rash. Blood work performed at this presentation revealed new-onset anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukocytosis with hemoglobin (Hb) of 10.6 g/dL (Reference range [RR]: 13–18 g/dL), platelet count (PC) of 129 × 103/μL (RR: 150–450 × 103/μL), and white blood cell count of 17,000/μL (RR: 4,000–11,000/μL), respectively. He had normal renal and hepatic function panels. His chest radiograph was normal. He was thought to have an upper respiratory tract infection, and he was treated with doxycycline for 10 days. In addition, given the new-onset bicytopenia, he was referred to his hematologist for further management.

His symptoms persisted despite doxycycline use. Physical examination was unrevealing for any new findings. Blood work was repeated which showed persistence of anemia (Hb: 10.6 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (PC: 143 × 103/μL). Reticulocyte was elevated at 5.1% (RR: 0.6–2.4%), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 453 U/L (RR: 120–246 U/L), and immunoglobulin G (IgG)/C3D direct Coombs test was weakly positive (1+). Given the laboratory evidence of hemolysis and direct Coombs positivity, he was thought to have autoimmune bicytopenia secondary to CLL. He was started on oral prednisone.

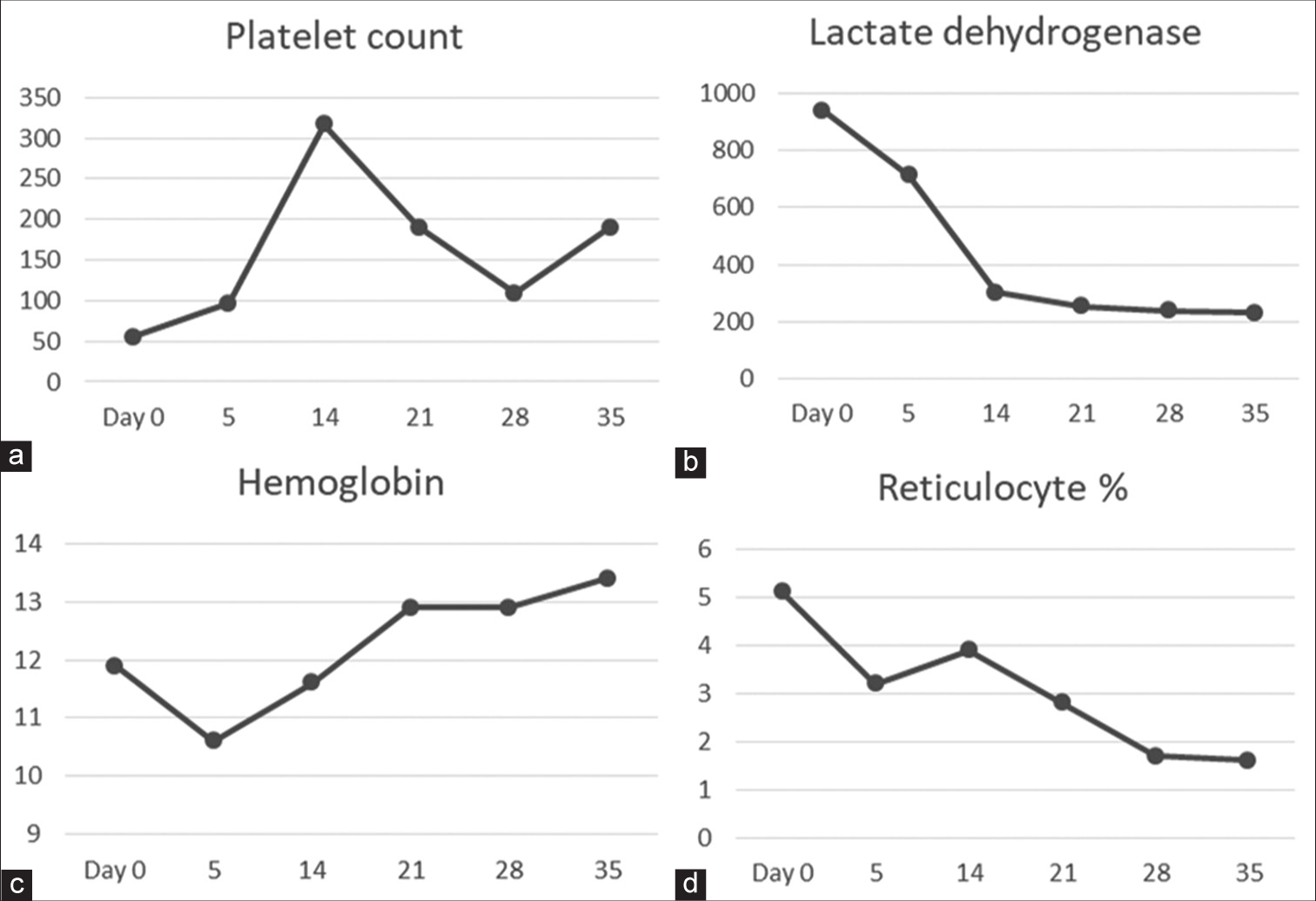

Despite 3 weeks of therapy, his PC further decreased to 55 × 103/μL, reticulocyte count increased to 5.5%, LDH increased to 940 U/L, while Hb increased slightly to 11.9 g/dL. Peripheral blood smear (PBS) was performed which showed the presence of intra-erythrocytic inclusions [Figure 1]. Babesia PCR was positive, while antibodies to Borrelia and Anaplasma were negative.

- Intra-erythrocytic inclusions seen in peripheral blood smear.

He was then referred to infectious disease where further pertinent history was obtained. He frequently had deer in his yard. His neighbor had Lyme disease past year. He had a dog, but he had not seen ticks on his dog. He denied any personal history of tick bites or blood transfusion. He had traveled extensively within the past 3 months to various states within the United States including Colorado, Georgia, West Virginia, and Maine for hiking and business reasons. He worked as an administrator in telecommunication company and lived in New York state.

He was treated with atovaquone and azithromycin for 6 weeks. He was monitored with weekly PBS. His PBS turned negative and continued to remain so after 2nd week. He remained on tapering dose of prednisone during this time. Blood counts recovered, as shown in Figure 2.

- (a-d) Trends of blood counts and hemolytic parameters after initiation of treatment for babesiosis. Day 0 is the 1st day of treatment.

DISCUSSION

One-third of patients with CLL develop autoimmune cytopenias in their lifetime.[1] The diagnosis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) in our case was initially made due to the presence of anemia, elevated markers of hemolysis, and weakly positive IgG and C3D direct Coombs test. He was appropriately treated with steroids, which is considered to be the first-line therapy.[2] The typical response rate to steroids ranges between 75 and 80%.[2] When hemolytic markers and thrombocytopenia continued to worsen despite administration of steroids, the initial inference was that this case might belong to the 20–25% of cases classified as steroid unresponsive. In addition, direct Coombs test has its own limitations. It produces falsely positive results in approximately 1 in 1000–1 in 14,000 individuals in the general population and in around 7–8% of hospitalized population.[3]

PBS showed the presence of intra-erythrocytic inclusions. PCR for Babesia microti returned as positive. Babesiosis is a parasitic disease of increasing public health concern, especially in the northeastern part of the United States.[4] Climate change, global warming, increasing white-tailed deer population, and increasing encroachment of nature by humans have all led to the increase in its incidence. Humans are the accidental hosts of Babesia. It is transmitted by the Ixodes tick, which also transmits Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and Powassan virus.[4] Although Babesia can also be transmitted through blood transfusions, the risk has substantially decreased after implementation of screening tests by the American Red Cross.[5]

The symptoms of babesiosis are determined mainly by host immunocompetence. In healthy individuals with intact immune function, Babesia may be asymptomatic since it may be cleared by the spleen without the need for any therapy.[6] However, in patients with immunosuppression or asplenia, it can lead to a variety of symptoms ranging from cytopenias to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Splenic infarct and rupture can lead to hemorrhagic shock. Splenic rupture usually and paradoxically occurs with modest enlargement of spleen.[7]

The diagnosis of babesiosis is made based on PBS and PCR. The classic finding seen in PBS is the maltese cross. Coinfection with Lyme disease and anaplasmosis must be excluded given the common tick that transmits these diseases. Treatment in immunocompromised patients consists of at least 6 weeks of therapy with azithromycin and atovaquone combination or clindamycin and quinine combination.[8] Patient is monitored using periodic blood smears. The duration of therapy depends on the clearance of parasites from peripheral blood. Exchange transfusion is needed in cases of severe parasitemia (>10%) or multiorgan dysfunction.[8]

Malaria, which shares pathophysiology with babesiosis, is known to precipitate AIHA due to exposure of red blood cell (RBC) antigens to immune system. Phosphatidylserine (PS) is membrane lipid which is normally not found on the surface of RBCs. After malarial infection, PS is expressed on the surface of RBCs. This leads to the development of antibodies to PS resulting in autoimmune hemolysis. AIHA during and after malaria is a well-recognized entity.[9] In our case, although PBS was classic for babesiosis and our patient’s travel history rendered malaria to be a less likely diagnosis, malaria would have been a consideration in our case if his travel history included malaria-endemic areas.

There are case series of concomitant AIHA with babesiosis as well as babesiosis preceding AIHA.[10,11] In this case, we believe that babesiosis was the major cause of the observed cytopenias since treatment with antimicrobials resulted in rapid improvement and allowed rapid tapering of his steroid.

Several important teaching points can be gleaned from our case. First, our case highlights the importance of reviewing PBS in any case with new cytopenias. Second, it reiterates the importance of taking a good travel history. Third, our case can serve as a segue to further research exploring the relationship between AIHA and babesiosis.

CONCLUSION

Our case highlights the fact that it is important to consider other differentials for hemolytic anemia in patients with CLL. Examination of peripheral blood smear is paramount and provides valuable diagnostic clues.

Acknowledgment

Kimberly Campione for providing the image.

Authors’ contributions

HK: involved in conception and design, collected the data, drafted the manuscript, and finally approved the version to be published. ZK: collected the data, drafted the manuscript, and finally approved the version to be published. PP: revised the manuscript, and finally approved the version to be published.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A comprehensive review. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:5804.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:647-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyse or not to lyse: Clinical significance of red blood cell autoantibodies. Blood Rev. 2015;29:369-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and outcomes of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in solid malignancy: An analysis of the National Inpatient Sample Database. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:543-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babesia blood testing: The first-year experience. Transfusion. 2022;62:135-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persistent parasitemia after acute babesiosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:160-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splenic complications of babesia microti infection in humans: A systematic review. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2020;2020:e6934149.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA): 2020 guideline on diagnosis and management of babesiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e49-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post-babesiosis warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:939-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with human babesiosis. J Hematol. 2021;10:41-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]