Translate this page into:

Coping with COVID-19 pandemic lockdown – The lady doctors perspective

*Corresponding author: Indu Bansal Aggarwal, Department of Radiation Oncology, Narayana Superspecialty Hospital, Gurgaon, Haryana, India. indubansal@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Aggarwal IB, Ganjiwale J, Parikh A, Trivedi N, Kaur S, Chennamaneni R, et al. Coping with COVID-19 pandemic lockdown – The lady doctors perspective. Indian J Med Sci 2021;73(2):164-9.

Abstract

Objectives:

This study is about the challenges faced by the women doctors in India during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and Methods:

We conducted an online survey in 2020 for women doctors who were professionally engaged in active patient management in India before the onset of the current pandemic.

Results:

A total of 260 valid responses were received. Only 28% (73/260) were able to provide at least 50% of professional services as compared to the pre COVID-19 lockdown period. Statistically significant differences related to emotional health (feelings), physical activity, changes in how family sees the lady professional, personal free time availability, and family bonding.

Conclusion:

COVID-19 has led to the following important concerns for professional women - academic productivity; work-life balance; missed opportunities for collaborating; mental health, the need for equity-minded academic leadership, and decision-making. Our study showed that majority were stressed during the COVID-19 lockdown – with the impact being highest among those giving more than 50% of their time to professional medical services outside their homes.

Keywords

Stress

Lifestyle

Female

Dual responsibility

Home

Work

Profession

Family

INTRODUCTION

Women have always shouldered a greater responsibility, especially in patriarchal societies. Professional women have to juggle professional and personal lives to maintain a fine balance.[1] Health-care professionals also face additional challenges in low- and middle-income countries which have been documented elsewhere.[2] Often the term physician burnout is used to transfer the blame on the victim, sweeping the root cause of the problem under the carpet.[3] The COVID-19 pandemic has swept across our world and added a significant new dimension to daily life, especially among female healthcare professionals.[4] However, true extend of the problem, its various facets and its impact in the hospital and at home has not been addressed. Nonstop duty stretching beyond 36 h at a time, being held accountable when the responsibility lies elsewhere, being soft targets for abuse and violence, not having adequate protection from administration or authorities, being falsely maligned by media were part of existing problems. When no punitive action is taken against perpetrators, the problems get compounded.

The new Hippocratic Oath, ratified on November 4, 2017, by World Medical Association puts the spotlight on the need to address health of healthcare professionals first.[3] The Oath now includes the statement “I will attend to my own health, well-being, and abilities to provide care of the highest standard.” It forces the rest of the world to acknowledge the fact that only if they ensure the health of doctor will they have the benefit of skills and knowledge during their own illness.

To document the challenges faced by the women doctors in India, we devised this study and are sharing the results in this manuscript.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We devised a Multiple Choice Questionnaire that included 17 statements [Appendix 1] for an online survey specifically for women doctors who were professionally engaged in active patient management in India before the onset of COVID-19 pandemic. They were invited to share their real world circumstances in dealing with their professional personal life with the additional burden imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The survey questions and answer options were simple enough for responders to complete it in <5 min. A unique link to the Google form permitted automatic collection and tabulation of responses (downloadable as a Google spreadsheet; Google, Mountain View, CA).[5] The survey links were shared through WhatsApp or email with health-care professionals who had previously registered for and participated in our online CME programs.[5] After eliminating duplicates, the remaining answers were tabulated and analyzed.

The data analysis was performed in STATA Version 14.2 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).[6] Descriptive analysis of the questions was done and data presented using frequency (%) associations between the two categorical responses were calculated applying a Chi-square test and statistical significance was considered for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 265 responses were received from lady allopathic doctors, of which 260 were valid (three were by those who were not active in management of patients before onset of COVID-19 and two were duplicates).

The COVID-19 pandemic lockdown had varying impact on the professional life of the responders. While 5% (13/260) were unable to perform any professional work, 32% (83/260) were able to continue working at 25% of their original workload. Another 35% (91/260) could continue between 25% and 50% of their professional work and only 28% (73/260) could provide more than 50% of services as compared to the pre-COVID-19 lockdown period.

In response to the question regarding experience of managing dual responsibility of professional medical services and home the participants gave interesting results. A clear majority (84%; 218/260) found it more challenging during the lockdown. A total of 26/260 (10%) experienced no difference and the remaining 6% (16/260) actually thought it was less challenging.

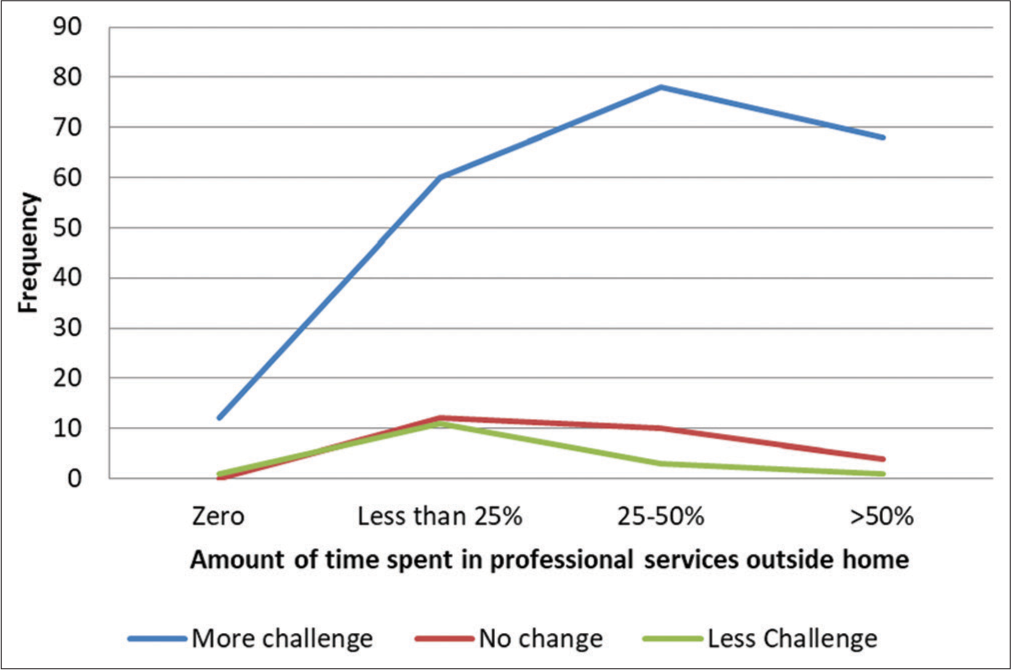

[Figure 1] compares the challenges faced in managing dual responsibility with the amount of time spent in providing professional services outside their homes.

- Challenges faced by respondents against the time they devoted for professional medical services outside home.

Attitude of the hospital administration (especially the human resource department) plays an important role in helping their staff cope with new challenges. The majority of the survey responders found no change in the attitude by their hospital administration toward lady doctors and nurses (55%; 143/260).

The attitude of family members was more flexible and sympathetic for 64% (165/260) of responders. It was unchanged for 28% (73/260) whereas the remaining 8.5% (22/260) faced less flexibility or sympathy at home.

As far as neighbors and other family members (not living in same household) were concerned, the responders felt no change in 70% (182/260). While 42/260 (16%) faced more hostility, the remaining 36/260 (14%) found neighbors to be more helpful.

Managing their own household chores and responsibilities remained unchanged only in 15% (40/260). While the majority (715; 185/260) found it easier than before, the remaining (13.5%; 35/260) found it more difficult.

While continuing with their responsibilities during the lockdown, the majority (48.5%; 126/260) felt stressed or irritated. In contrast, 72/260 (28%) felt relaxed or being happy. The remaining (24%; 62/260) experienced no change.

Daily physical activities were significantly increased in the majority (168/260; 65%), remained unchanged in a small fraction (12%; 32/260), and reduced in the remaining (60/260; 23%).

The dominant change that the responders faced from their family was a feeling of support, happiness and being relaxed (138/260; 53%). The remaining were almost equally divided between experiences no change (63/260; 24%) and those who faced irritation, boredom, or worry from family members (59/260; 23%).

As far as personal “me” time is concerned, 122/260 (47%) faced reduction, 109/260 (42%) had more time, and the remaining found no change (29/260; 11%).

Free time at home was spent in varying fashion by the responders. Spending quality time with family was the experienced by 116/260 (45%). Second most common was watching screens (Mobile, TV, and Social Media) experienced by 57/260 (22%). Activities helping professional development were carried out by 37/260 (14%) and 14/260 (5%) started engaging in a hobby. The remaining (14%; 36/260) did not participate in either of the options.

The majority (153/260; 59%) found it bothersome to cope with limited resources (house help, groceries, and consumables). At the other end, 63/260 (24%) found it easy to deal with lockdown restrictions and the remaining felt no change (44/260; 17%).

Physical distancing and inability to go out of home to socialize did not bother 118/260 (45%). Another 83/260 (32%) felt no change. The small remaining percentage (23%; 59/260) found it upsetting.

During the lockdown restrictions, family bonding was improved in 157/260 (60%) instances. In 73/260 (28%), there was no change whereas the remaining (30/260; 11.5%) found it adversely affected family bonding.

The lockdown experience made 145/260 (56%) value the services of household help more. On the other hand, 67/260 (26%) realized that they could cope without household assistance. The remaining (48/260; 18.5%) felt no change.

When asked about how the lockdown experience shall alter their approach to work life balance, the majority (138/260; 53%) said they would make significant changes which would continue after the lockdown was over. A total of 93/260 (36%) were not sure whereas the remaining (29/260; 11%) did not feel that their work life balance would return to original level.

When analyzing for association between the parameters and the percentage of time the lady doctors were devoting to providing professional medical services outside her home, the Chi-square test identified that five factors were linked with statistical significance [Table 1].

| During the current COVID-19 pandemic lockdown what is the % of time you are devoting to providing professional medical services outside your home | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero | Less than 25% | 25– 50% | Greater than 50% | |||

| While facing lockdown, your feelings | ||||||

| Relaxed/happy | 4 | 35 | 24 | 9 | 0.003 | |

| Same/no change | 1 | 18 | 23 | 20 | ||

| Stressed | 8 | 30 | 44 | 44 | ||

| Change in your physical activity | ||||||

| Increased | 12 | 46 | 56 | 54 | 0.011 | |

| Reduced | 1 | 28 | 18 | 13 | ||

| No change | 0 | 9 | 17 | 6 | ||

| Dominant change toward you that you see in your family (those living with you) | ||||||

| No change | 0 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 0.047 | |

| Happy/active/ relaxed/ supportive | 9 | 52 | 48 | 29 | ||

| Unhappy/bored/ irritated/worried | 4 | 14 | 21 | 20 | ||

| Has your personal free time changed during lockdown | ||||||

| It has increased | 3 | 45 | 42 | 19 | 0.004 | |

| It has reduced | 10 | 29 | 39 | 44 | ||

| Same – no change | 0 | 9 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Has lockdown affected family bonding | ||||||

| No change | 3 | 18 | 30 | 22 | 0.011 | |

| Yes, stressed bonding | 2 | 3 | 10 | 15 | ||

| Yes, improved bonding | 8 | 62 | 51 | 36 | ||

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that majority of our participants was stressed during the COVID-19 lockdown. Not surprisingly, the ones giving more than 50% of their time to professional medical services outside home were more stressed than others [Table 1]. Need for physical activity increased for all responders. Once again, the increase was commensurate with time spend in professional medical duties.

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic has been profound on working women especially because of dual responsibilities of workplace and home. Female healthcare workers are no exception.[7-12]

COVID-19 has led to six major concerns for women: Academic productivity; work-life balance; missed opportunities for collaborating; mental health, the need for equity-minded academic leadership and decision-making; and missing a career-advancing promotion that may have led to improved economic standing.[1,11,12]

There are almost 100 million female workers in health and care institutions around the world, balancing work and family responsibilities.[4] In 2017, almost half of all doctors in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries were women and they represent close to 70% of the Global Healthcare Workforce according to an analysis of 104 countries conducted by the World Health Organization.[7] Globally, women represent the majority of nurses and midwives.[9] At present, they are on the front line of the fight against COVID-19.

Although women dominate the industry overall, few women advance to leadership positions and they lead just 19% of hospitals. When it comes to companies in the health-care industry, women only hold 13% of CEO roles and 33% of senior leadership positions. Unfortunately, there is a 28.0% gender wage gap in healthcare around the globe and women in healthcare are paid less, on average, than their male counterparts.[9,10]

The research landscape is uneven as well, with the portion of women lead authors in 2020 on COVID-19-related papers being 23% lower than their representation among lead authors in 2019.[11] Because of more household responsibilities females are getting even less of protected time for research and many have left the job, cut down on their working hours or are thinking of quitting jobs because of increased demand at home. In our analysis, only 28% (73/260) could provide more than 50% of services as compared to the pre-COVID-19 lockdown period.

Women as front line healthcare workers are at increased risk of being infected by COVID-19. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control reports that, as of April 2020, 73% of healthcare professionals who tested positive for COVID-19 were women.[12]

Almost half of the physicians suffer from burnout (46.58%) during their professional career. Among senior consultant level doctors, the incidence of burnout is usually 33% and can be as high as 60%. Male doctors have 14 times higher risk of committing suicide than other men. Its risk is even higher among female doctors – 23 times higher than the general female population.[3]

Even before the pandemic, women physician-researchers did more parenting and domestic work than men in similar positions, totaling 8.5 additional hours per week. In our survey, a clear majority (84%; 218/260) found it more challenging during the lockdown. The pandemic, along with its associated closure of schools, childcare, and other care facilities have heavily increased the daily time spent in unpaid care work.[4,7,9] Fortunately, in our study, family members were actively supportive to lady doctors [Table1]. However, this support seemed to be more for those spending <25% of their time to professional medical duties. Juggling professional responsibilities and domestic work also eats up into their free time [Table 1].

In spite of these challenges, including discrimination faced, women are very resilient and able to adapt to changing circumstances. This was confirmed in our survey. Physical distancing and inability to go out of home to socialize did not bother 118/260 (45%). Another 83/260 (32%) felt no change. Less than a quarter of our responders (23%; 59/260) found it upsetting for not being able to socialize with friends.

Our study showed that family bonding improved for some – especially among those who spent <50% of their time for outside professional commitments [Table 1]. When asked about how the lockdown experience shall alter their approach to work life balance, the majority (138/260; 53%) of respondents in the survey, said they would make significant changes which would continue after the lockdown was over. More than 20 women physicians and scientists recently warned that the pandemic could lead to “a hemorrhaging of women from academia.”[11] A worldwide shortage of about 18 million healthcare workers is projected by 2030.[7] The World Health Organization suggests this shortage, a consequence of anticipated demographic changes and economic growth, could be mitigated by gender equality initiatives.[8]

We need to work on changing an undesirable dynamic.[13-15] Mothers are traditionally “the designated parent” even if they are working. Taking care of daily errands as laundry, shopping, cleaning, and cooking are mandatory and these tasks fall on women. If only sharing of the mundane work could make all the difference. In our survey, the attitude of family members was more flexible and sympathetic for 64% (165/260) of responders. It was unchanged for 28% (73/260) whereas the remaining 8.5% (22/260) faced less flexibility or sympathy at home. As far as neighbors and other family members (not living in same household) were concerned, the responders felt no change in 70% (182/260). While 42/260 (16%) faced more hostility the remaining 36/260 (14%) found neighbors to be more helpful. The majority (153/260; 59%) found it bothersome to cope with limited resources (house help, groceries, and consumables).

Females also have the mental load of the planning, scheduling, coordinating, prioritizing, and problem-solving. In addition, females who are lactating are the child’s first lunch box and sometimes she has to leave the job because of skeletonized childcare services at workplace.[16] As far as personal “me” time is concerned, 122/260 (47%) faced reduction in our study.

Using personal protective equipment was a new experience for healthcare workers. Using them for prolonged duration was a greater challenge for women, especially while having monthly periods with no loo break or a 12 h long shift.[12] As per our analysis, while continuing with their responsibilities during the lockdown, the majority (48.5%; 126/260) felt stressed or irritated. Daily physical activities were significantly increased in the majority (168/260; 65%).

An overt gender bias is due to general personal believes about women (as women are less committed to their careers than men or believing that women make less effective leaders than men).[17,18] Because of these reasons identical work done by females is consistently rated lower by evaluators (both male and female) and women have to give more proof than men (e.g. more publications or award) to convince “raters” of their professional competence.[19]

This explains why the majority of the survey responders found no change in the attitude by their hospital administration toward lady doctors and nurses (55%; 143/260). Sensitivity to women’s needs did not change. Just as children are not young adults, women are not differently looking males.[20] They have unique needs that must be taken into consideration at all times.[21]

The few solutions to this gender inequality are (1) to provide women with flexible work schedules and robust child care supports, (2) family supportive workplace culture, (3) rethinking of awards for academic and organizational efforts, (4) to proactively help women advance their careers, (5) inclusive leadership, (6) to include women in interview committees, (7) equal compensation for women, (8) institutional responsiveness, (9) babysitter bonus, (10) providing childcare and eldercare services at workplace, (11) facility for providing online groceries at workplace, (12) measures to identify physician burnout and (13) psychological counseling.[8,10,11,13,16,18,21]

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives forever in many ways. Let it also be an opportunity to acknowledge the true contribution of women healthcare workers and give them due recognition at the workplace and at home. Let us move beyond “fixing the women” to a systemic, institutional approach that systematically devalues and marginalizes women.[18] We want more women to sit at “the office table” and more men to sit at “the kitchen table.” As more women take greater responsibilities in their professional careers, more men need to shoulder equal share of responsibilities to their families. We ladies should also resist the habit of “maternal gatekeeping” Let’s enable men to feel more empowered at home. It is not about biology. It is more about consciousness. It is not just the mask that can protect women physicians from COVID-19 aftermath. Let us put a tiara on a woman’s head, in the jungle gym when she needs it the most.

CONCLUSION

COVID-19 has led to the following important concerns for professional women – academic productivity; work-life balance; missed opportunities for collaborating; and mental health, the need for equity-minded academic leadership, and decision-making. Our study showed that majority were stressed during the COVID-19 lockdown – with the impact being highest amongst those giving more than 50% of their time to professional medical services outside their homes.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- COVID-19 and Women in the Workforce, Penn Today. 2021. Available from: https://www.penntoday.upenn.edu/news/covid-19-and-women-workforce [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 22]

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender climate in Indian oncology: National survey report. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000671.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnout in healthcare professionals-epidemic that is swept under the carpet. Indian J Med Sci. 2017;69:1-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: Protecting Workers in the Workplace: Women Health Workers: Working Relentlessly in Hospitals and at Home. 2021. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/wcms_741060/lang--en/index.htm [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 07]

- [Google Scholar]

- South Asian declaration-consensus guidelines for COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients. South Asian J Cancer 2021

- [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://www.stata.com/stata14 [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 14]

- Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries. 2020. Available from: https://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311314 [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 22]

- [Google Scholar]

- Women in Healthcare: Quick Take, Catalyst. 2020. Available from: https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-healthcare [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Minding the gap: Organizational strategies to promote gender equity in academic medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3681-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy Weiner: How COVID-19 Threatens the Careers of Women in Medicine. 2020. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-covid-19-threatens-careers-women-medicine [Last accessed on 2021 Feb 06]

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenges for the female health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The need for protection beyond the mask. Pulmonology. 2021;27:1-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID 19 and Gender Equality: Countering the Regressive Effects, McKinsey and Company. 2020. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/covid-19-and-gender-equality-countering-the-regressive-effects [Last accessed on 2021 Mar 17]

- [Google Scholar]

- 'Elastic band strategy': Women's lived experience of coping with domestic violence in rural Indonesia. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has COVID-19 had a greater impact on female than male oncologists? Results of the ESMO women for oncology (W4O) survey. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100131.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family leave and return-to-work experiences of physician mothers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1913054.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is there still a glass ceiling for women in academic surgery? Ann Surg. 2011;253:637-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Why is John more likely to become department Chair than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:197-214.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women's health and women's leadership in academic medicine: Hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:1453-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://www.medium.com/thrive-global/wtf-guys-women-deserve-better-112b03b2e6b0 [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 20]

- Gender equality in the global health workplace: Learning from a SomalilandUK paired institutional partnership. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e001073.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]