Translate this page into:

Hypertensive retinal changes: It’s prevalence and associations with other target organ damage

*Corresponding author: Soumya Ray, Department of Ophthalmology, Burdwan Medical College, Bardhaman, West Bengal, India. soumyaray0308@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ray S, Sahu BK, Naskar S. Hypertensive retinal changes: It’s prevalence and associations with other target organ damage. Indian J Med Sci 2020;72(3):195-200.

Abstract

Objectives:

This study enlightens association of different cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and renal morbidities with hypertensive retinopathy which is very much relevant in the present scenario, especially in India, where the prevalence of hypertension is very high. The objectives of the study were to estimate the prevalence, association, and severity of hypertensive retinal changes among patients with other target organ damage (TOD) such as cardiovascular or cerebrovascular or renal morbidities.

Material and Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive observational study was carried out after doing systemic random sampling involving 416 study participants having a history of hypertensive cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and renal damages include history of stroke, acute coronary syndromes, left ventricular hypertrophy, and chronic kidney disease which were examined by direct ophthalmoscopy findings and classified according to the Scheie classification throughout the past 1 year in OPD of our institution.

Results:

Hypertensive retinopathy was present in 259 patients (62.25%) out of 416 participants (Grade I: 13.5%, Grade II: 26.9%, Grade III: 18.5%, and Grade IV: 3.4%). Among the variables associated with hypertensive retinopathy, it was seen that 209 (63.3%) subjects present with features of hypertensive retinopathy are more than 50 years of age. No significant association was found between hypertensive retinopathy and presence or absence of cardiovascular morbidities, cerebrovascular morbidities, and renal morbidities. However, the subgroup analysis shows that significant association was found between Grade IV hypertensive retinopathy with renal morbidities (odds ratio [OR] = 5.83 at 95% CI, P = 0.002) and Grade I retinopathy with cerebrovascular morbidities (OR = 7.09 at 95% CI, P = 0.000).

Conclusion:

Severe grades of retinopathy can be an indicator of renal morbidity, whereas earlier grades of retinopathy can be predictor of acute cerebrovascular events. Physicians should adopt holistic approach to evaluate TODs and screen them adequately in all hypertensives.

Keywords

Hypertensive retinopathy

Stroke

Acute coronary syndromes

Left ventricular hypertrophy

Chronic kidney disease

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 26% of the adult population are affected by hypertension in world. It has been estimated that the prevalence of hypertension would increase by 24% in developed countries and in developing countries, it is 80% by 2025.[1] About 57% of all stroke deaths and 24% of all cardiovascular deaths in East Asians are reported to be related with hypertension.[2] Eyes are known to be hypertensive target organs.[3] It was shown that the cardiovascular risk factors staging in hypertensive patients is based on retinopathy changes.[4]

Some ophthalmoscopy findings are helpful in evaluating hypertensive vasculopathy effects.[5]

Retinal microvascular changes can be useful to classify risk factors and treatment decisions for hypertension.[6]

It has long been well recognized that hypertensive retinopathy can be a predictor of systemic morbidity and mortality. Several epidemiological and clinical studies have provided evidence that markers of hypertensive retinopathy are associated with raised blood pressure, systemic vascular diseases, and subclinical cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease, and predict incident of clinical stroke, congestive heart failure, and mortality due to cardiovascular complications.

According to the previous doctrine of international hypertension management, including JNC7 and British Hypertension Society,[7,8] hypertensive retinopathy can be evaluated as an indicator for the target organ damage (TOD) along with the left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and chronic renal failure and suggested that physicians should adopt a more aggressive approach in the management of these patients.[8] However, in other reviews, association of hypertensive retinopathy with other TOD has been shown to be independent of blood pressure and other risk factors, which supports the recommendation that retinal vascular changes should be assessed in individuals with systemic hypertension for better extraocular TOD risk stratification.[7] While the number of reports on hypertensive TOD has been on the rise, the relationship between hypertensive retinopathy and other TOD has largely remained unexplored. The objective of this study is to examine the association of hypertensive retinopathy with other end organ damage such as cardiovascular/cerebrovascular/renal morbidities.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was an institution-based observational cross-sectional study.

After obtaining approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee, study was conducted. The study subjects were recruited from the patients attending OPD of general medicine in each Wednesday.

Inclusion criteria

Hypertensive patients diagnosed to have cardiovascular or cerebrovascular or renal morbidities which are known to be caused by hypertensive end organ damage giving consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were excluded from the study:

Patients having preexisting retinal vasculopathy changes other than hypertension

Patients having diabetes

Patients having preexisting media opacity such as corneal opacity and cataract that precludes dilated fundus examination

Patients taking retinotoxic drugs like chloroquine

Patients not willing to give consent.

The previously diagnosed hypertensive patients having either cardiovascular and/or cerebrovascular and/or renal morbidities consistent with hypertensive changes that are ischemic/hemorrhagic stroke, acute coronary syndromes, LVH, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) by thorough review of the previous laboratory data of previous investigations suggestive of end organ damage (such as serum urea, creatinine for CKD, ECG findings, and troponin t-test for acute coronary syndromes, echocardiography, and/or electrocardiography for LVH, CT/MRI brain suggestive of ischemic/hemorrhagic stroke).

Systematic random sampling was performed. After taking consent and detailed history, they were evaluated by dilated fundoscopy and findings were included in case record form. One drop of tropicamide 0.8% and phenylephrine 5% was given every 15 min for 1 h to dilate pupil. Hypertensive retinopathy was graded based on Scheie classification for hypertensive retinopathy [Table 1].[9] Evaluation of hypertensive retinopathy was performed by one examiner by direct ophthalmoscopy in all cases to avoid any interobserver variation.

| Grade | Features |

|---|---|

| 0 | Diagnosis of hypertension but no visible abnormalities |

| 1 | Diffuse arteriolar narrowing no focal constriction |

| 2 | More pronounced arteriolar narrowing with focal constriction |

| 3 | Focal and diffuse narrowing with retinal hemorrhage |

| 4 | Retinal edema, hard exudate, and optic disc edema |

All data were collected in a single visit. Data were collected and entered into Excel sheets and analyzed by appropriate statistical methods.

RESULTS

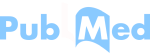

Hypertensive retinopathy was present in 259 patients (62.25%) out of 416 participants (Grade I: 13.5%, Grade II: 26.9%, Grade III: 18.5%, and Grade IV: 3.4%) [Table 2]. Figure 1 shows Distribution of the study subjects according to end organ damage and status of hypertensive retinopathy.

- Distribution of the study subjects according to end organ damage and status of hypertensive retinopathy.

| Gender | Hypertensive retinopathy | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent No. (%) | Present | |||||

| Grade I No. (%) | Grade II No. (%) | Grade III No. (%) | Grade IV No. (%) | |||

| Male | 37 (34.6) | 7 (6.5) | 28 (26.2) | 21 (19.6) | 14 (13.1) | 107 (100) |

| Female | 120 (38.8) | 49 (15.9) | 84 (27.2) | 56 (18.1) | 0 | 309 (100) |

| Total | 157 (37.7) | 56 (13.5) | 112 (26.9) | 77 (18.5) | 14 (3.4) | 416 (100) |

Chi-square value 46.062, df 4, P=0.000

Among the variables associated with hypertensive retinopathy, it was seen that 209 (63.3%) subjects present with features of hypertensive retinopathy were more than 50 years of age [Table 3].

| Co variants | Hypertensive retinopathy | COR (CI) | AOR (CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent No. (%) | Present No. (%) | ||||

| Age | |||||

| ≤50 | 36 (39.1) | 56 (60.9) | Ref | Ref | |

| >50 | 121 (36.7) | 209 (63.3) | 1.34 (0.80–2.23) | 0.27 | |

| LVH | |||||

| Absent | 101 (34.9) | 188 (65.1) | Ref | Ref | |

| Present | 56 (42.1) | 77 (57.9) | 0.74 (0.49–1.13) | 0.69 (0.37–1.29) | 0.24 |

| Cerebrovascular morbidity | |||||

| Absent | 79 (39.9) | 119 (60.1) | Ref | Ref | |

| Present | 78 (34.8) | 146 (65.2) | 1.24 (0.84–1.85) | 1.09 (0.61–1.95) | 0.78 |

| Renovascular morbidity | |||||

| Absent | 134 (37.5) | 233 (62.5) | Ref | Ref | |

| Present | 23 (35.4) | 42 (64.6) | 0.91 (0.53–1.58) | 0.92 (0.51–1.65) | 0.77 |

Apparently, it seems that in overall analysis, no significant association was found between hypertensive retinopathy and presence or absence of cardiovascular morbidities (32% vs. 68%, χ2 = 51.96, df = 4, P = 0.000), cerebrovascular morbidities (52.4% vs. 47.6%, χ2 = 36.356, df = 4, P = 0.000), and renal morbidities (15.6% vs. 84.4%, χ2 = 16.399, df = 4, P = 0.003) [Table 3].

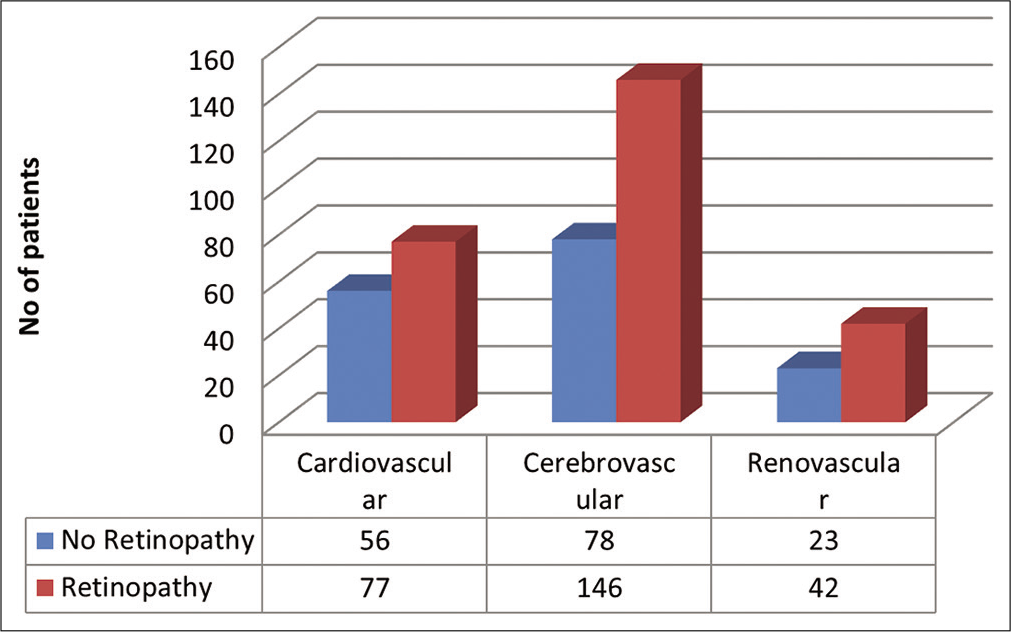

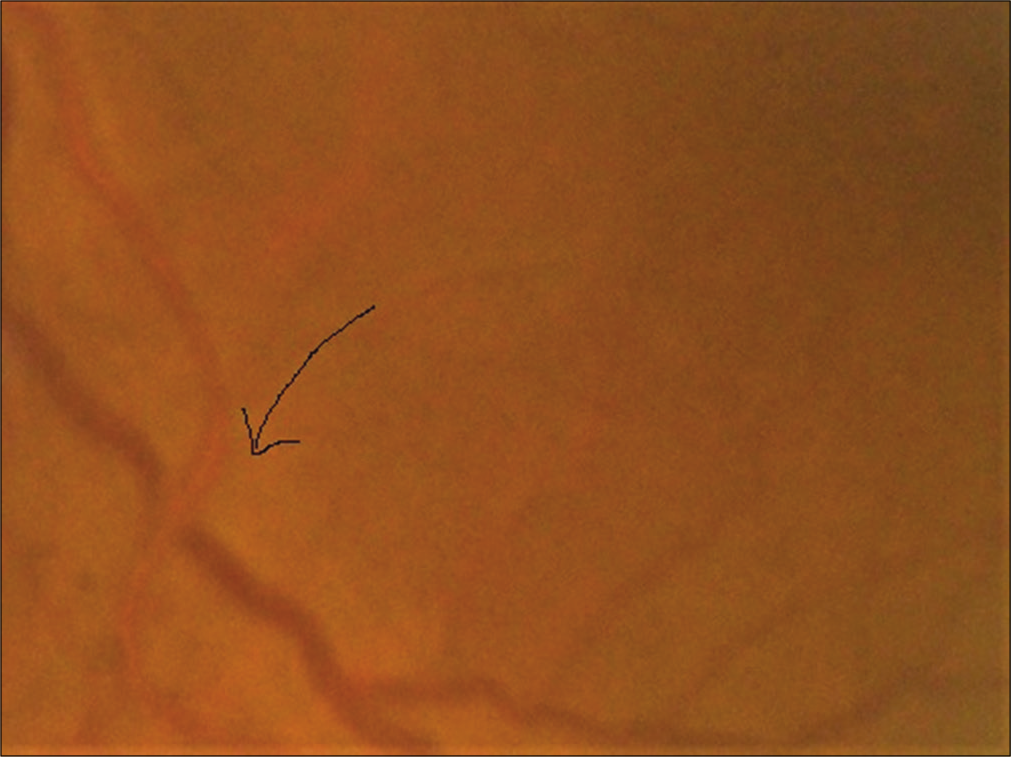

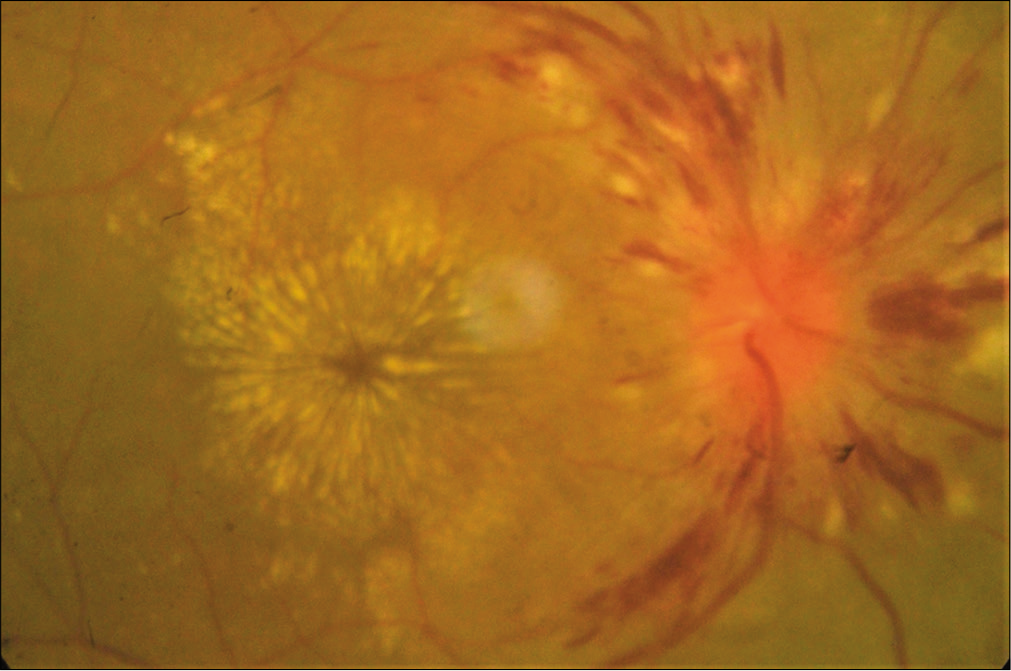

Whereas the subgroup analysis shows that statistically significant association was found between Grade IV hypertensive retinopathy with renal morbidities (odds ratio [OR] = 5.83 at 95% CI, P = 0.002) [Table 4] and Grade I retinopathy with cerebrovascular morbidities (OR = 7.09 at 95% CI, P= 0.000) [Table 5]. However, no such statistically significant association was found in case of hypertensive retinopathy and cardiovascular morbidity [Table 6]. Several clinical photos have added here as in Figure 2 shows Salus sign: Acute deflection of retinal vein by the compression of atherosclerotic artery. Figure 3 shows Generalized arteriolar constriction: Grade 1 hypertensive retinopathy and Figure 4 shows Hypertensive retinopathy Grade 4: Disc edema with flame-shaped hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, and macular edema with star-shaped exudate deposition.

- Salus sign: Arrow showing acute deflection of retinal vein by the compression of atherosclerotic artery.

- Generalized arteriolar constriction: Grade 1 hypertensive retinopathy

- Hypertensive retinopathy Grade 4: Disc edema with flame-shaped hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, and macular edema with star-shaped exudate deposition.

| Retinopathy grade | With renovascular disease No. (%) | Without renovascular disease No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | Chi-square | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 23 (14.6) | 134 (85.4) | 1 | ||

| 1 | 7 (12.5) | 49 (87.5) | 0.83 (0.34–2.06) | 0.692 | |

| 2 | 21 (18.8) | 91 (81.2) | 1.34 (0.70–2.57) | 0.371 | |

| 3 | 7 (9.1) | 70 (90.9) | 0.58 (0.24–1.43) | 0.236 | |

| 4 | 7 (50) | 7 (50) | 5.83 (1.87–18.17) | 0.002 | |

| Total | 65 (15.6) | 351 (84.4) |

Chi-square 16.399, df 4, P=0.003

| Retinopathy grade | With cerebrovascular disease No. (%) | Without cerebrovascular disease No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | Chi-square | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 78 (49.7) | 79 (50.3) | 1 | ||

| 1 | 49 (87.5) | 7 (12.5) | 7.09 (3.03–16.61) | 0.000 | |

| 2 | 56 (50) | 56 (50) | 1.01 (0.62–1.65) | 0.959 | |

| 3 | 28 (36.4) | 49 (63.6) | 0.58 (0.33–1.01) | 0.056 | |

| 4 | 7 (50) | 7 (50) | 1.01 (0.34–3.02) | 0.982 | |

| Total | 218 (52.4) | 198 (47.6) |

Chi-square 36.356, df 4, P=0.000

| Retinopathy grade | With cardiovascular disease No. (%) | Without cardiovascular disease No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | Chi-square | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 56 (35.7) | 101 (64.3) | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 56 (100) | 0.00 | 0.997 | |

| 2 | 35 (31.2) | 77 (68.8) | 0.82 (0.45–1.37) | 0.450 | |

| 3 | 42 (54.5) | 35 (45.5) | 2.16 (1.24–3.77) | 0.006 | |

| 4 | 0 | 14 (100) | 0.00 | 0.998 | |

| Total | 283 (68) | 133 (32) |

Chi-square 51.95, df 4, P=0.000

DISCUSSION

Among Indian studies that correlate hypertensive retinopathy with hypertensive systemic complications, study by Singh et al. showed age distribution pattern was similar to our study in essential hypertension and hypertensive retinopathy patients. Changes in retinal vessels were almost always associated with systemic complications. A close correlation between local, ocular, and systemic complications of hypertension was also established.[10]

In our study, 62.25% of patients had hypertensive retinopathy changes which corroborates with the findings of Gupta et al.[11] In an extensive literature search, the highest level of prevalence of hypertensive retinopathy among hypertensives was found among Congolese patients leading to peak level of 83.6%.[12]

About 65.4% of males and 61.2% of females had retinopathy. About 34.6% of males and 38.8% of females had no signs of retinopathy; there was no significant sex preponderance which corroborates with Gupta et al.[13] and other studies. There are fewer studies in literature of hypertensive retinopathy and none of them have shown sex preponderance.

In our study, there was an increased incidence of hypertensive retinopathy in older age group. Age distribution pattern showed that 63.3% of patients of hypertensive retinopathy are >50 years of age group. This corroborates with the findings of Singh et al.[10] and Mondal et al.[13] that age distribution pattern was similar in essential hypertension and hypertensive retinopathy. This finding also suggests that age-related sclerosis is a key factor of developing hypertensive changes in blood vessels.

Contrary to the famous CRIC study, our study does not show any significant statistically association (P = 0.24) between hypertensive retinopathy with cardiovascular morbidity including LVH. This observation corroborates with Kabedi et al.[12] in their observations among Congolese patients as well as other studies like Shirafkan et al.[14]

Similarly, no statistically significant association was found between hypertensive retinopathy and cerebrovascular morbidity (P = 0.78). This observation corroborates with the findings of Kabedi et al.[12] Whereas many cross-sectional studies have demonstrated a clear relationship between hypertensive ocular fundoscopic abnormalities with cerebrovascular morbidity like strokes.[15-17]

Overall hypertensive retinopathy and renal changes do not seem to be statistically significant (P = 0.77) which again corroborates with the findings of Kabedi et al.[12] However, subgroup analysis showed that significant association was found only between Grade IV hypertensive retinopathy with renal morbidities (OR = 5.83 at 95% CI, P = 0.002). This corroborates with CRIC study[18] and other studies time to time. It has been hypothesized that both hypertension-related retinal and renal vascular changes share common pathogenic mechanisms. Hence, retinal vascular changes associated with hypertension and lower GFR.[18-20] Whereas the moderate grades of hypertensive retinopathy (Grade I, II, and III) having lower number of OR (0.83, 1.34, and 0.58) signify weaker association with renal changes. As severe grades of retinopathy are also associated with prolonged duration of hypertension which again directly related with CKD. Hence, CKD changes are more associated with Grade IV hypertensive retinopathy.

Significant statistically association has been established in case of Grade I retinopathy with cerebrovascular morbidities (OR = 7.09 at 95% CI, P = 0.000). Grade I retinopathy present in 87.5% of patients of cerebrovascular morbidity, Grades II, III, and IV have decreasing number of patients having cerebrovascular morbidity. This trend signifies that acute transient change in blood pressure is associated with Grade I retinopathy as well as cerebral acute events like stroke.

Regarding the association of hypertensive retinopathy with cardiovascular morbidity including LVH, our study observed that Grade II retinopathy was associated with 31.2% and Grade III retinopathy with 51.5% (significant OR 2.16) cardiovascular morbidity patients, whereas no patients with cardiovascular morbidity had Grade I or Grade IV retinopathy. Corroborating with the observations of Cuspidi et al.,[21] our study also finds that the frequency of severe retinopathy is low among the patients of cardiovascular morbidity. As duration of hypertension is strongly associated with cardiovascular morbidity, especially LVH,[14] it may be concluded that our patients had moderate duration of hypertension so only Grade II and Grade III hypertensive retinopathy patients had cardiovascular morbidity. Grade I retinopathy is associated with transient rise of blood pressure which may not be sufficient to cause detectable changes of heart, whereas sustained hypertension causes Grade IV retinopathy. This findings is as per with Shirafkan et al.[14]

Limitations of the study

As no study is beyond its own limitations, we also have some limitations. Lack of availability of sophisticated imaging to diagnose early changes in retinopathy as well as cerebrovascular and renal changes limits our diagnosis. Besides, small study samples also contribute to its limitations. Further, we only adopted direct ophthalmoscopy which has limited benefit in the management of hypertension due to very low prevalence of Grade 3 and Grade 4 hypertensive retinopathies, the multifactorial backgrounds of Grade 1 and Grade 2 hypertensive retinopathies and the association of the multiple risk factors of atherosclerosis in a majority of hypertensive cases.[22]

CONCLUSION

Very few studies worldwide as well as in India corroborate relation and association among different hypertensive TOD. There is deficiency in documented data to estimate the prevalence of hypertensive retinopathy among the patients with hypertensive TOD. We observed that only severe grades of retinopathy can be an indicator of renal morbidity, whereas earlier grades of retinopathy can be predictor of acute cerebrovascular events. Physicians should adopt holistic approach to evaluate TODs and screen them adequately in all hypertensives.

Acknowledgment

We feel gratitude to the faculties and staffs of the department of general medicine and ophthalmology for directly and indirectly helping to compile the study.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217-23.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reducing the global burden of blood pressure related cardiovascular disease. J Hypertens. 2000;18:S3-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Do angiographic data support a detailed classification of hypertensive fundus changes? J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:405-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of retinal vascular changes in never-treated essential hypertensive: An Inter and intra-observer reproducibility study with nonmydriatic retinography. Blood Press. 2004;13:25-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypertensive retinopathy and incident coronary heart disease in high risk men. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1002-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British hypertension society guidelines for hypertension management 2004 (BHSIV): Summary. BMJ. 2004;328:634-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of ophthalmoscopic changes of hypertension and arteriolar sclerosis. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1953;49:117-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of hypertensive retinopathy in patients of essential hypertension with high serum lipids. Med J DY Patil Univ. 2013;6:165-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hypertensive retinopathy and its association with cardiovascular, renal and cerebrovascular morbidity in Congolese patients. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2014;25:228-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors of hypertensive retinopathy in hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2017;6:241.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Association between left ventricular hypertrophy with retinopathy and renal dysfunction in patients with essential hypertension. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:1177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Retinal microvascular abnormalities and MRI-defined subclinical cerebral infarction: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 2006;37:82-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Associations between findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging and retinal photography in the elderly: The cardiovascular health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:78-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retinopathy as an indicator of silent brain infarction in asymptomatic hypertensive subjects. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252:159-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retinopathy and chronic kidney disease in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:1136-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creatinine clearance and signs of end-organ damage in primary hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:511-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of ocular fundus pathology in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:867-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and correlates of advanced retinopathy in a large selected hypertensive population. The evaluation of target organ damage in hypertension (ETODH) study. Blood Press. 2005;14:25-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funduscopic examination has limited benefit for management of hypertension. Int Heart J. 2007;48:187-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]