Translate this page into:

The pathway to comfort: Role of palliative care for serious COVID-19 illness

*Corresponding author: Pankaj Singhai, Department of Palliative Medicine and Supportive Care, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal - 576104, Karnataka, India. pankaj.singhai@manipal.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Rao KS, Singhai P, Salins N, Rao SR. The pathway to comfort: Role of palliative care for serious COVID-19 illness. Indian J Med Sci 2020;72(2):95-100.

Abstract

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has led to significant distress among people of all age groups. Patients with advanced age and severe life-limiting illnesses are at increased risk of death from COVID-19. Not all patients presenting with severe illness will be eligible for aggressive intensive treatment. In limited resource setting, patients may be triaged for supportive care only. This subset of patients should be promptly identified and receive appropriate palliative care with adequate symptom control strategies and psychosocial support. Breathlessness, delirium, pain, and noisy breathing are main symptoms among these patients which can add to the suffering at end-of-life. The COVID-19 pandemic also contributes to the psychological distress due to stigma of the illness, uncertainty of the illness course, fear of death and dying in isolation, and anticipatory grief in families. Empathetic communication and holistic psychosocial support are important in providing good palliative care in COVID-19 patients and their families.

Keywords

COVID-19

Coronavirus

Palliative care

End-of-life care

Communication

Psychological support

INTRODUCTION

Why palliative care in COVID-19 illness?

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and its mitigation measures have resulted in a humanitarian crisis and are redefining the global health-care scenario. With millions affected, the World Health Organization (WHO) is reporting an average death rate between 2% and 4%, with the death rate among elderly patients at 15–22%.[1] Patients with severe life-limiting illnesses such as advanced cancer, end-stage organ impairment, comorbidities, and the elderly are at increased risk of mortality from COVID-19. Triaging policies set according to local exigencies might triage this subset of patients with severe COVID-19-related respiratory illness to receive only supportive care.[2,3] Those with serious acute respiratory illness secondary to COVID-19 not receiving or not eligible to receive aggressive intensive care management should receive appropriate symptom management measures.[4] As much as physical repercussions of the disease demands attention, the mental health issues also need to be addressed.

What is palliative care?

Palliative care, with a biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care, is an active holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness and especially of those near the end-of-life.[5] It emphasizes on early identification of symptoms and its control, empathetic communication, psychosocial and spiritual support, end-of-life care, and bereavement care.

Who should receive palliative care in a humanitarian crisis?[6]

A subset of the population with COVID-19 will develop severe symptom burden and respiratory distress. Not all will be eligible for aggressive intensive care management due to their underlying conditions, especially those who are elderly with multiple comorbidities, end-organ impairment, and advanced cancer.[3] When the health-care system is overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients, and the resources are limited, these patients may be triaged for supportive treatment only. This guideline addresses the symptom management and supportive care strategies in patients with serious COVID-19 illness not suitable for intensive care treatment and ventilation.

COVID-19 patients not suitable for ventilation are categorized as stable, unstable, and end-of-life. The categorization is based on the early warning parameters recommended by the National Health Service and WHO.[7,8] The parameters used in categorization are early warning scores, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation [Tables 1 and 2].[9]

| Stable | a. EWS ≤7 |

| b. RR ≤25/min | |

| c. O2saturation >88% (on 60% venturi mask) | |

| Unstable | a. EWS >7 |

| b. RR>25/min | |

| c. O2saturation <88% (on 60% venturi mask) | |

| End-of-life | a. ARDS |

| b. O2saturation <70% |

| SCORE→ | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (C) | <35 | 35.1–36 | 36.1–38 | 38.1–39 | >39 | ||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | <41 | 41–50 | 51–90 | 91–110 | 111–130 | >130 | |

| Systolic BP (mm/Hg) | <91 | 91–100 | 101–110 | 111–219 | >219 | ||

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | <9 | 9–11 | 12–20 | 21–24 | >25 | ||

| Oxygen saturation (%) | <92 | 92–93 | 94–95 | >96 | |||

| Supplemental oxygen | Yes | No | |||||

| CNS response | GCS>12 | GCS<12 |

Palliative care triaging in COVID-19 is classified into four categories [Table 3]. In the patients with code blue and red, palliative care should be integrated with the acute services and disaster response team for rapid and emergency palliative care.

| Category | Color code | Description | Palliative care involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | Red | Survival only possible with immediate treatment | Emergency palliative care integrated with active care anddisaster response |

| Expectant | Blue | Survival not possible given the care available | Emergency palliative care integrated with active care anddisaster response |

| Delayed | Yellow | Not in immediate danger of death but treatment needed | Palliative care as required for symptom management |

| Minimal | Green | Will need medical treatment sometime in the future | Palliative care may be required for relief of symptoms |

(Reproduced with permission from Salins et al., 2020)20

ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF COMMON SYMPTOMS IN COVID-19 PATIENTS

COVID-19 patients and their families with severe acute respiratory illness experience debilitating symptoms, physical and psychological, that need assessment and management.

Physical symptom management

The physical symptoms could be due to the direct effect of COVID-19, exacerbation of pre-existing condition, or side effects of the treatment. In this review, we will be discussing the symptoms that are caused by the direct effect of COVID-19. Breathlessness, delirium, respiratory secretions, and pain are the common symptoms that need immediate attention [Table 4].[10]

| Management of dyspnea[21,22] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mild dyspnea (VDS score 1–3) | Moderate dyspnea (VDS score 4–6) | Severe dyspnea (VDS score 7–10) |

| Medical management | Strategies used for mild dyspnea | Strategies used for mild dyspnea |

| High flow oxygen | + | + |

| Positioning (upright, sitting, leaning forward) | Oral morphine immediate release 2.5 mg BD-TDS + 2.5 mg SOS. Slow upward titration by 2.5 mg daily up to | Inj. morphine 2 mg iv Q4H + Inj. midazolam 2 mg SC Q4H |

| Cold flannel on the face | 40–60 mg/day | Inj. morphine 10–15 mg + Inj. midazolam 10–15 mg as a 24 h infusion |

| Oral lorazepam 0.5 mg if anxiety is present. Increase by 0.5 mg daily up to | ||

| 4 mg/day | ||

| Management of delirium and agitation in patients with serious COVID-19 infections[23,24] | ||

| Mild delirium | Delirium with agitation | Agitation/restlessness without delirium |

| Non pharmacological: | Non-pharmacological strategies for mild delirium | Mild symptoms: |

| Quiet room | + | Non-pharmacological strategies used for mild delirium + relaxation therapies if possible |

| Less visual/auditory excitation | Pharmacological: | Tab. lorazepam 0.5 mg HS titrated by 0.5 mg up to 4 mg |

| Bed by the side of window | Inj. haloperidol 2.5 mg IV Q6H-Q8H | Severe symptoms: |

| Reorientation techniques | Inj. haloperidol 5–10 mg/24 h continuous IV infusion | Inj. midazolam 2 mg SC/IV Q4H or ascontinuous SC/IV infusion |

| Consistency of the nursing staff | If agitation not controlled add | 10–15 mg/24 h |

| Avoiding physical restraints | Inj. midazolam 2 mg IV Q4H or as continuous IV infusion 10–15 mg/24 h | |

| Pharmacological: | ||

| Oral haloperidol 0.5 mg BD and titrate dose upward to a maximum of 10–15 mg/24 h | ||

| Avoid benzodiazepines if possible | ||

| Managing respiratory secretions[25] | ||

| Non-pharmacological management | Pharmacological management | |

| Optimizing hydration | Inj. glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg Q8H to Q6H IV if severe 0.8 to 1.4 mg/24 h in divided doses or as a continuous IV infusion over 24 h | |

| Judicious use of parenteral hydration | ||

| Avoiding oropharyngeal suctioning | ||

| Preventing aspiration | ||

| Lateral recumbent position head slightly raised | ||

| Management of pain in patients with COVID-19[22,26] | ||

| Mild pain (NRS: 1–3) | Moderate pain (NRS: 4–6) | Severe pain (NRS: 7–10) |

| Oral paracetamol 2–4 g/24 h in four divided doses | Strategies used for mild pain | Strategies used for mild pain |

| If patient is not taking orally | + | + |

| Inj. paracetamol 2–4 g/24 h in four divided doses | Oral morphine immediate release 5 mg Q4H and breakthrough dose is 1/6th the 24 h dose. Upward titration by 50% of dose everyday | Inj. morphine 2–2.5 mg iv Q4Hr/ Inj. morphine 10–15 mg as a 24 h infusion |

| If neuropathic pain is present | If patient unable to take orally Inj. morphine 1–2 mg IV every 4 h | Consider fentanyl if patient has renal failure. Fentanyl dose is |

| Start gabapentin 100 mg HS and upward titration by 100–300 mg/24 h to a maximum of | Consider fentanyl if patient has renal failure. Fentanyl dose is 0.2–0.5 mcg/kg/h | 0.2–0.5 mcg/kg/h |

| 2700–3600 mg/24 h | Other strategies for managing constipation if patient is unable to take oral bisacodyl | |

| Avoid NSAIDs | ||

Dyspnea can develop in COVID-19 patients with severe acute respiratory symptoms.[11] The intensity of dyspnea can be assessed using visual dyspnea scale and appropriate management can be initiated. Delirium is common in patients with acute and serious illness needing ICU care or at the end-of-life either due to sepsis, metabolic disturbances, cerebral hypoxia, or medications. Patients with delirium may have varied presentation from hypoactive to/or mixed type of delirium with fluctuating levels of activation which needs to be recognized and managed.[12] Respiratory secretions seen in 20–90% of patients in the last days or hours of life can be very distressing. Interventions focused at reducing secretions aim to alleviate the distress of the care providers, even though the patients may not be aware of this.[13] Etiology of pain in an ICU setting could be multifactorial and can be due to illness per se or due to medical procedures and invasive interventions. Proper assessment and management prevents distress and suffering of the patients and their families and aims at providing good end-of-life care.[14]

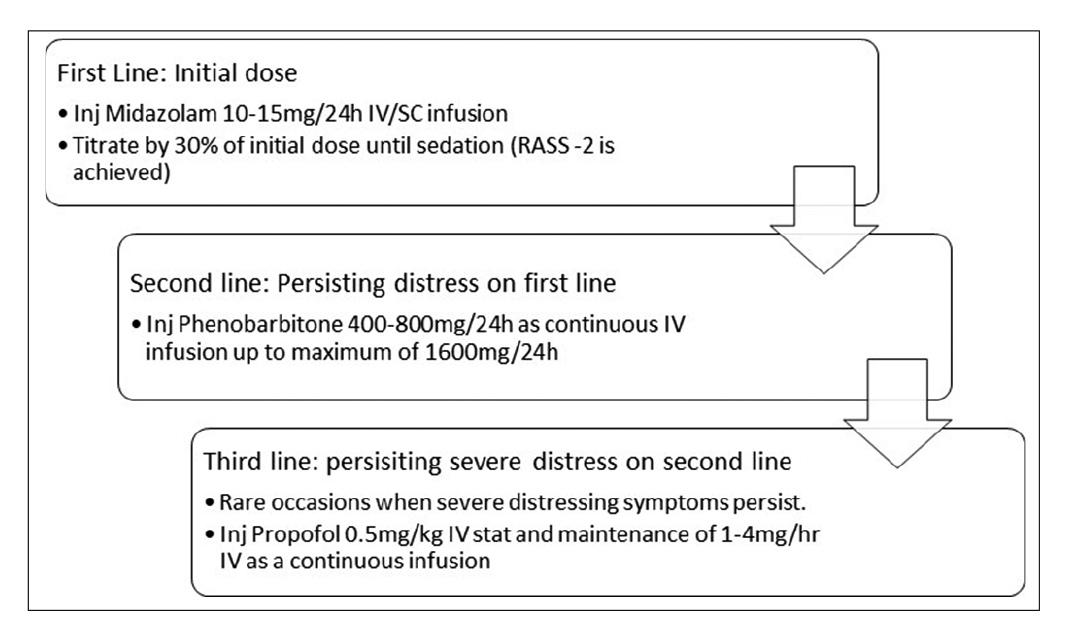

Management of intractable symptoms

In a subset of patients, adequate relief of symptoms with the above measures may not be possible. These patients can experience increased distress and are best managed by administering medications to induce a state of decreased awareness. Palliative sedation is used to relieve the suffering caused by intractable symptoms.[15]

PRE-REQUISITES FOR INITIATING PALLIATIVE SEDATION AND STEP-WISE APPROACH [FIGURE 1]

Assessment to ascertain irreversibility of the clinical condition and symptoms

Communication to family regarding refractory symptoms and lack of effective strategies to manage within a reasonable period of time

Sensitive information sharing and shared decision-making

Informed consent

Documentation of clinical condition, prognostication of illness, proposed approach, probable duration of sedation, and any anticipated side effects.

End-of-life symptom management of serious COVID-19 patients not ventilated or discontinued ventilation

Patients who are not ventilated or discontinued from ventilation can develop severe breathlessness, delirium, and moist breathing. A combination of medications either as a continuous infusion or intermittent dosing along with breakthrough medications can be administered to such patients.[16] Anticipatory prescription would help address the specific symptoms at end-of-life and reduce distress [Table 5].

| Symptom anticipated | Treatment plan |

|---|---|

| Pain | Inj. morphine 1–2 mg IV/SC sos or q4h |

| Breathlessness | Inj. morphine 1–2 mg IV/SC sos or q4h |

| Distress/agitation | Inj. midazolam 1–2 mg IV/SC sos or q4h |

| Delirium | Inj. haloperidol 1–2 mg IV/SC sos or q4h |

| Delirium with severe agitation | Inj. haloperidol 1–2 mg IV/SC + |

| Inj. midazolam 1–2 mg IV/SC sos or q4h | |

| Respiratory secretions | Inj. glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg IV/SC sos or q4h |

| Nausea and vomiting | Inj. metoclopramide 20 mg IV/SC sos or q4h |

Psychosocial support

Patients and their families diagnosed with COVID-19 undergo a great deal of suffering caused by the physical manifestation of the disease, the uncertainty, fear of illness and death, stigma, and the socioeconomic hardships. Palliative care focuses on alleviating suffering, both physical and psychological. The various aspects of psychosocial distress among patients with COVID-19, their caregivers, and health-care providers are outlined below and recommendations provided for their management.

Communication tips for health-care providers during COVID-19

Many health-care providers find communicating the diagnosis and prognosis in the setting of serious illnesses challenging, more so during the COVID-19 pandemic. The physical distancing norms, the PPE, the stigma, and lack of time and skill, and the sudden deterioration that occurs in this setting make these conversations extremely difficult.

Health-care providers need to communicate effectively to

To share information in a timely, clear, and precise manner with patients/families

To treat patients nearing end-of-life and their families with dignity and compassion

To promote collaboration between patients/families and health-care providers and local bodies to ensure adherence to public health norms.

Steps for communicating with patients affected by COVID-19 and their families[10,17,18]

Ensure comfort

Check emotions

Reassure the family and patients

Assess need for information and elicit concerns

Deliver information with empathy

Acknowledge and validate emotions

Address anger and explore reason. Call for help if the patient/caregiver is violent/agitated or in the presence of a mob.

- Stepwise approach for palliative sedation.

Skills for communicating in times of crisis to discuss resource allocation[10,18]

Explain the ICMR guidelines for the management of COVID-19

Explain what this means to the patient – Talk about what you will do first and then what you cannot do

Assert what care you will provide

Respond to emotion

Reassure that there is no bias for any patient and same protocol applies to everyone.

Loss, grief, and bereavement

Patients and families diagnosed with COVID-19 experience a profound sense of loss. Most of them are unprepared for the rapid deterioration in health. This is coupled with other losses such as the sense of security, livelihood, financial security, personal freedom, and support systems. Grief is the response to the event of loss. Bereavement is the loss experienced due to the death of a loved one. Family members who are unable to be at the bedside of their dying patients or see them one last time may experience feelings of guilt and remorse. Loss, grief, and bereavement can be complicated in critically ill COVID-19 patients and their families. Attending to this distress in an important component of palliative care service provision.

Steps to handle grief and bereavement[18]

Recognize distress

Recognize grief

Rule out psychiatric morbidity

Initiate grief interventions - Supportive psychosocial and grief interventions

Referral to mental health experts in case of complicated/ difficult grief.

Psychosocial distress

Patients with COVID-19 and their families are likely to experience increased distress from the time of diagnosis, during quarantine/isolation, when the patient becomes symptomatic, or when the illness worsens and finally leads to death. The psychological morbidity can start immediately or can develop later. What is known is that the mental health effects of the pandemic extend beyond the period of the pandemic leading to short-term and long-term psychiatric morbidity. Patient/ families seeking palliative care in this situation are likely to be in extreme distress and assessing and managing distress is an important part of palliative care service provision.[10]

Pathway for assessing psychosocial distress involves following steps

Screening for distress

Explore current concerns

Evaluate risks

Assign risk stratification to appropriate therapy.

Managing of psychosocial issues in critically ill patients with COVID-19 and their families

Psychoeducation which involves giving honest information in simple and accurate messages, avoiding false reassurances, maintains a calm behavior while sharing information with groups of affected people, families are an important aspect of psychosocial care. Support to enhance coping includes providing reassurance, facilitating ventilation and validation of feelings, helping normalize anger and grief, and promoting realistic hope and goal setting. Psychotherapeutic techniques such as cognitive restructuring, relaxation techniques, yoga, mindfulness, problem-solving therapy, and social skills training have proven efficacy in crisis situations. Addressing spiritual distress by reestablishing connectedness, therapies to foster meaning and purpose at end-of-life like dignity conserving care and therapy, meaning-centered psychotherapy, acceptance, and commitment therapy enhance well-being at end-of-life.[19] Pharmacological management is indicated in the presence of psychiatric illness along with supportive therapy. Drug of choice for anxiety and depression is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as escitalopram 10–20 mg/day or sertraline 50–200 mg/day. In COVID-19, patients may experience panic, insomnia, and anxiety due to diagnosis, uncertain disease course, fear, and stigma of the disease. In such patients’ shorter-acting benzodiazepines like lorazepam, 1–2 mg can be prescribed. However, care should be taken to taper and stop the same once the patient is better, as benzodiazepines have addictive potential. Agitation, psychotic episodes, and delirium could be managed with antipsychotic medications such as haloperidol 2.5–5 mg/day or olanzapine 5–10 mg/day.[10,18]

CONCLUSION

COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as a global health threat causing socioeconomic and health-care crisis worldwide. Triaging of COVID-19 patients with serious illness who are not eligible for mechanical ventilation or those patients who are not responding to ventilation is important. In these patients, withholding or limiting life-sustaining treatment is indicated and provision of adequate symptom control and end-of-life care is considered appropriate. Integration of palliative care in COVID care pathway is essential for decision making, symptom management and end of life care including bereavement.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- The Role of Palliative Care in a COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available from: https://www.csupalliativecare.org/palliative-care-and-covid-19 [Last accessed on 2020 05 10]

- [Google Scholar]

- The toughest triage-allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1973-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1773-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395:931-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Redefining palliative care-a new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. ;2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief into Responses to Humanitarian Emergencies and Crises: A WHO Guide Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) when COVID-19 Disease is Suspected: Interim Guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization;. ;2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians, National Early Warning Score (NEWS) London: Standardising the Assessment of Acute- illness Severity in the NHS; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conservative management of Covid-19 patients-emergency palliative care in action. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e27-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care for advanced cancer patients in the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and adaptations. Cancer Res Stat Treat. 2020;3(Suppl S1):127-3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420-2.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:66-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benefits of interventions for respiratory secretion management in adult palliative care patients-a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- It's not just about pain: Symptom management in palliative care. Nurse Prescr. 2014;12:338-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ESMO clinical practice guidelines for the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life and the use of palliative sedation. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):143-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medication and monitoring in palliative sedation therapy: A systematic review and quality assessment of published guidelines. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:734-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/covid-19-communication-skills [Last accessed on 2020 May 10]

- Available from: https://www.palliumindia.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/e-book-Palliative-Care-Guidelines-for-COVID19-ver1.pdf [Last accessed on 2020 May 10]

- End-of-life care policy: An integrated care plan for the dying: A joint position statement of the Indian society of critical care medicine (ISCCM) and the Indian association of palliative care (IAPC) Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:615-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symptom management and supportive care of serious COVID-19 patients and their families in India. 2020. Indian J Crit Care Med. Available from: https://www.ijccm.org/doi/IJCCM/pdf/10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23400

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of Refractory Dyspnoea: Evidence-based Interventions Australia: Australian Cancer Society; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adapting management of sarcomas in COVID-19: An evidence-based review. Indian J Orthop. 2020;2020:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of haloperidol infusions to control delirium in critically ill adults. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:690-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions to prevent and treat delirium in older patients: a systematic overview. The SENATOR project ONTOP series. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123090.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noisy respiratory secretions at the end of life. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3:120-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Structured approaches to pain management in the ICU. Chest. 2009;135:1665-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]