Translate this page into:

Imaging features of hydatid cyst in unusual locations: A case series

*Corresponding author: Kundur Alekya, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Apollo Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. alekyakundur@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Alekya K, Meraj MD, Moorthy NLN. Imaging features of hydatid cyst in unusual locations: A case series. Indian J Med Sci. doi: 10.25259/IJMS_198_2024

Abstract

Hydatid disease (HD) is a parasitic infection primarily caused by Echinococcus granulosus, frequently affecting the liver and lungs. However, the disease can manifest in uncommon locations, making diagnosis challenging due to its atypical presentation. This case series presents five instances of hydatid cysts in rare locations, including the kidney, breast, thigh muscles, retroperitoneum, and orbit, each confirmed by imaging and histopathology. The imaging features were characteristic of HD but required careful consideration to avoid misdiagnosis. In the kidney, a large multiloculated cyst with daughter cysts necessitated partial nephrectomy. The breast hydatid cyst presented as a painless lump, with imaging confirming a Type III (CE3b) lesion, leading to successful surgical excision. A retroperitoneal cyst, presenting with vague abdominal pain, required extensive surgery due to its complex nature. The thigh muscle cysts, which were multiloculated and invasive, necessitated a more extensive surgical approach. Finally, the orbital hydatid cyst, although rare, was successfully managed with surgical excision and adjunctive albendazole therapy. This series emphasizes the importance of considering HD in differential diagnoses, especially in endemic regions, even when the cysts are located in atypical anatomical sites. Early diagnosis through imaging and appropriate surgical and medical management is crucial in preventing complications and recurrence.

Keywords

Hydatid cysts

Echinococcus granulosus

Uncommon locations

INTRODUCTION

Hydatid disease (HD) or echinococcosis is a parasitic infection caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, commonly found in livestock-raising regions like India. Humans are accidental hosts, often infected through contact with dogs or by ingesting eggs in contaminated food, water, or soil. Once ingested, the eggs hatch in the small intestine, releasing oncospheres that penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the bloodstream, forming hydatid cysts in various organs.[1] While hydatid cysts predominantly occur in the liver (70%) and lungs (20%), they can also develop in less common locations, accounting for <10% of cases. These rare presentations often mimic other conditions, complicating the diagnosis.

Imaging plays a crucial role in diagnosing HD. Although ultrasound is typically used initially, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential for further characterization of the cysts and guiding treatment. Key imaging features include daughter cysts, membrane detachment, and cyst wall calcifications. Given the rarity of hydatid cysts in locations such as the breast, kidney, intramuscular areas, retroperitoneum, and orbit, this case series contributes to the literature by detailing the imaging features and clinical presentations of five cases. Recognizing these features is vital for early diagnosis and management, particularly in patients from endemic areas.

CASE SERIES

Case 1

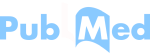

A 45-year-old female presented with the right flank pain lasting six months. Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) of the abdomen revealed a large hypoattenuating cystic lesion in the right kidney, with multiple peripherally arranged daughter cysts forming a characteristic “cartwheel” appearance, suggestive of a hydatid cyst [Figure 1]. Serology confirmed the diagnosis. The patient underwent partial nephrectomy, followed by uneventful post-operative recovery and albendazole therapy to prevent recurrence.

- A 45-year-old female presented with the right flank pain. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography image shows a large hypo attenuating cystic lesion in the right kidney with multiple peripherally arranged daughter cysts of varying sizes within, giving “cartwheel” appearance, suggestive of a hydatid cyst in the right kidney.

Case 2

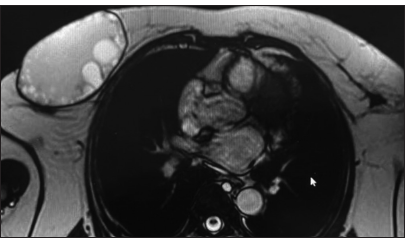

A 53-year-old female presented with a palpable lump in her right breast. MRI showed a well-defined, thin-walled cystic lesion with multiple small daughter cysts, consistent with a Type III (CE3b) hydatid cyst [Figure 2]. Surgical excision of the cyst was performed, and histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of hydatid cyst.

- A 53-year-old female presented with a palpable lump in her right breast. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a well-defined thin-walled predominantly hyperintense lesion with multiple small cysts (daughter cysts) within it in the right breast; Features consistent with a Type III (CE3b) hydatid cyst.

Case 3

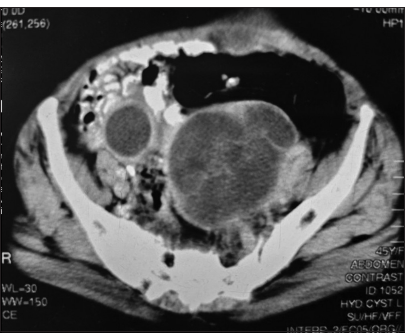

A 45-year-old male presented with intermittent abdominal pain. Blood tests showed mild eosinophilia, while liver and renal function tests were normal. CECT revealed a large multiloculated cystic lesion in the retroperitoneum, with enhancing walls and septations, indicating a hydatid cyst [Figure 3]. Serological tests confirmed the diagnosis. The patient underwent surgical excision, and histopathological examination validated the presence of hydatid cysts.

- A 45-year-old male with intermittent abdominal pain. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography abdomen image shows a large, well-defined, multiloculated hypodense cystic lesion in the retroperitoneum with enhancing walls and septations, findings indicative of a retroperitoneal hydatid cyst. Surrounding inflammatory changes and displacement of the adjacent bowel loops seen.

Case 4

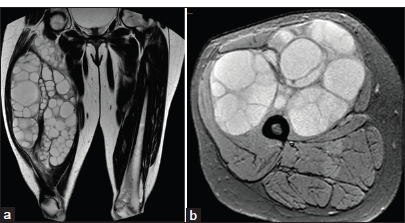

A 28-year-old female reported a progressively enlarging, painless swelling in her right thigh over 6 months. MRI revealed multiple multiloculated cystic lesions in the anterior muscle group of the right thigh [Figure 4], consistent with intramuscular hydatid cysts. The cysts were surgically excised, and histopathology confirmed HD. The patient recovered well post-surgery and was advised to continue albendazole therapy to prevent recurrence.

- A 28-year-old female presented with swelling in the right thigh. (a) Coronal T2W and (b) axial T2 FS images of magnetic resonance image show multiple multiloculated hyperintense cystic lesions with a hypointense rim in the anterior muscle group of the right thigh, favoring a diagnosis of intramuscular hydatid cyst. FS: Fat suppression.

Case 5

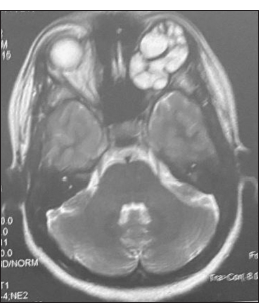

A 21-year-old female presented with proptosis of the left eye. MRI revealed a multiloculated cystic lesion in the left orbit and similar lesions in the left cerebral hemisphere, consistent with orbital and cerebral HD [Figure 5]. Surgical excision confirmed the diagnosis of an orbital hydatid cyst, and the patient was treated with adjunctive albendazole postoperatively.

- A 21-year-old female with proptosis of the left eye. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the orbit shows a hyperintense, multiloculated cystic lesion in the left orbit with hypointense rim and septations, consistent with hydatid cyst.

DISCUSSION

HD, primarily caused by E. granulosus, mostly affects the liver and lungs. However, its occurrence in atypical locations such as the kidney, breast, orbit, thigh muscles, and retroperitoneum is rare but clinically significant. Transmission to unusual sites typically occurs through systemic dissemination rather than direct infection. Hydatid cysts can metastasize to distant organs through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Gharbi et al.[2] emphasized that hematogenous spread is a primary mechanism for developing cysts in unusual locations such as the kidneys and muscles. In cases of cysts in the orbit and breast, the mode of transmission is likely due to embolization from primary hepatic or pulmonary cysts. Macpherson and Coles[3] noted that while the orbit and breast are uncommon sites, systemic spread from primary lesions remains the main route of infection. Hydatid cysts exhibit characteristic imaging features that vary with the cyst’s stage and location. Early-stage cysts typically appear as unilocular, well-defined fluid-filled lesions on imaging modalities such as ultrasound, CT, and MRI. As the cyst matures, internal septations or daughter cysts may develop, giving it a “honeycomb” or “rosette” appearance. In later stages, degenerative changes may lead to the “water-lily” sign, where floating membranes are visible within the cyst. Advanced cysts may calcify, appearing dense with associated shadowing on imaging. Table 1 presents the classification of hydatid cyts on imaging according to both the WHO and Gharbi systems.[4]

| WHO-IWGE 2001 | Gharbi 1981 | Description | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| CE 1 | Type I | Unilocular unechoic cystic lesion with double line sign | Active |

| CE2 | Type III | Multiseptated, “rosettelike” honeycomb cyst | Active |

| CE3 A | Type II | Cyst with detached membranes (waterlilysign) | Transitional |

| CE3 B | Type III | Cyst with daughter cysts in solid matrix | Transitional |

| CE4 | Type IV | Cyst with heterogenous hypoechoic/hyperechoic contents. No daughter cysts | Inactive |

| CE5 | Type V | Solid cyst with calcified wall | Inactive |

WHOIWGE: World Health OrganizationInformal Working Groups on Echinococcosis, CE: Cystic echinococcosis

Renal hydatid cysts account for about 2–3% of all cases. Pedrosa et al.[5] reported that renal hydatid cysts were often Gharbi Type I or II, treated with nephron-sparing surgery or cystectomy. In contrast, our case involved a Gharbi Type III cyst, necessitating nephrectomy due to its multilocular and extensive nature, reflecting an advanced stage. Breast hydatid cysts are extremely rare, with an incidence of <0.27%. Atalay et al.[6] and Kiresi et al.[7] reported cases often misdiagnosed as neoplastic masses. Our patient presented with a painless, slowly enlarging mass. Imaging-based diagnosis and surgical excision were performed, avoiding fine needle aspiration cytology due to the risk of rupture, as highlighted in previous cases. Retroperitoneal hydatid cysts are among the rarest, with an incidence ranging from 0.2% to 0.9%. They usually present with nonspecific symptoms such as vague abdominal pain or a palpable mass, as described by Akhan et al.[8] Yaghan et al.[9] noted that while these cysts are indeed rare, they generally allow for simpler surgical interventions. Our case, involving a large multilocular cyst with extensive involvement of adjacent structures, required a more complex surgery, contrasting with simpler interventions previously reported. Muscular hydatid cysts constitute <3% of all cases. Turgut et al.[10] and Petik and Aksoy[11] reported simple excisions for such cysts. Our case involved a multilocular cyst in the thigh muscles, requiring extensive surgery due to its invasive nature, in contrast to the simpler cases reported earlier. Orbital hydatid cysts are very rare, accounting for <1% of cases. Ghaffari et al.[12] reported simple excisions of orbital cysts. Our case involved a Gharbi Type III and World Health Organization CE2 cyst, necessitating careful excision and adjunctive albendazole therapy to minimize recurrence risks.

The management of hydatid cysts varies based on location and associated complications. Surgical resection is preferred for cysts in the kidney, breast, and retroperitoneum, allowing for complete cyst removal and reduced recurrence risk. For cysts in more sensitive areas, such as the orbit and muscles, a combination of surgery and antiparasitic medication, particularly albendazole, is often used. This combination approach is critical for managing cysts in challenging anatomical locations or when complete excision poses a high risk of spreading the cyst content. Medical therapy alone, primarily with antiparasitic drugs like albendazole or mebendazole, is typically insufficient to eradicate the cysts entirely. However, these medications play an essential role in reducing cyst size, preventing further spread, and minimizing recurrence following surgery.[13,14]

CONCLUSION

HD can present in uncommon anatomical locations, complicating diagnosis as cysts in rare sites may mimic other conditions. Despite characteristic imaging findings, differential diagnosis can be challenging, even in patients from endemic regions. However, in such areas, hydatid cysts should be considered whenever cystic lesions are encountered. This case series underscores the importance of high clinical suspicion, detailed imaging evaluation, and a combined surgical and medical management approach to achieve favorable outcomes and prevent recurrence. Familiarity with imaging characteristics is crucial, as HD can affect any part of the body that the bloodstream reaches.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that they have used ChatGPT to refine and rephrase the text.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Detection, screening and community epidemiology of taeniid cestode zoonoses: Cystic echinococcosis, alveolar echinococcosis and neurocysticercosis. Adv Parasitol. 1996;38:169-250.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Systemic dissemination of hydatid cysts: mechanisms and implications. Infect Dis J. 2012;23:124-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncommon locations of hydatid cysts: A literature review. Parasitol Int. 2013;62:32-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Echinococcosis from head to toe: A pictorial review Vienna: The European Congress of Radiology; 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydatid cyst of the breast: A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:274-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncommon locations of hydatid cysts. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:622-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retroperitoneal hydatid cysts: A report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:335-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydatid cyst of the breast: A case report and literature review. Am J Surg. 2004;188:325-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Muscular hydatid cyst: A review of 8 cases. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29:425-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Unusual locations of hydatid disease: Diagnostic and management challenges. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2013;57:640-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Orbital hydatid cyst: A case report and review of the literature. Int Ophthalmol. 2004;25:47-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical management of hydatid cysts: outcomes and strategies. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:783-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical therapy for hydatid disease: Current perspectives. Parasite Ther Prev. 2019;14:201-8.

- [Google Scholar]