Translate this page into:

Patient centric integrative supportive care model at a tertiary cancer care center of India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Sushma Bhatnagar, Professor and Head, Department of OncoAnaesthesia and Palliative Medicine, Dr. B.R.A IRCH and NCI, Jhajjar, AIIMS, New Delhi, Delhi, India. sushmabhatnagar1@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Patel A, Bhatnagar S, Ratre B. Patient centric integrative supportive care model at a tertiary cancer care center of India. Indian J Med Sci 2021;73(2):275-80.

Abstract

Palliative care is emerging as a recognized and needed branch all over the country. Integration of palliative care with oncology enhances patient’s quality of life, decreases suffering and depression, ensures good end of life care, better patient’s satisfaction, and decreases cost by avoiding unnecessary chemotherapy or ventilator support. The aim of this narrative analysis is to provide a truly integrated supportive model of palliative care practiced at DR BRA IRCH, AIIMS, Delhi, a tertiary cancer care center in India. It consists of inpatient and outpatient services with round the clock consultation teams. Integration of palliative care with other oncology has helped us in providing holistic and comprehensive care to the patients. We aim that this model might help in creating patient centric comprehensive care model in various other cancer centers with limited resources.

Keywords

Palliative care

Oncology

Palliative care model

Patient centric

INTRODUCTION

We at Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital (DR BRA IRCH) started palliative services with few staffs and mere resources but dedicated team. We did not have any inpatient services. Hence, we started providing consultation services regarding pain and palliative care to various other departments. Medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists gradually accepted palliative care need of their patients as patients were more satisfied and started seeking palliative care teams. Gradually, we expanded our department services by including six bedded inpatient wards and providing outpatient services as well. “Patient centric Integrative Supportive care model” practiced at DRA BRA IRCH is a model where patient is at the center and various other departments are dedicated to achieve the best possible care and management of the patients. In India, around 1 million new cases are diagnosed each year but <2% in need receives services of palliative care.[1] Palliative care in India has been started a long time back almost 30 years ago.[2] First palliative care unit was established in Montreal, Canada, in 1976.[3] In India, the very first form of palliative care service was started in Mumbai as a hospice in 1986.[4] However, palliative care services are inadequate and available only in limited regions.[5,6] India stands badly in terms of Quality of Death as per Economist Intelligence Unit.[7] Rural areas in India hardly have any awareness or access to palliative care.[8] Because of the better medical facility, life expectancy of people is increasing.[9] Thus, there is an increased burden of both cancer and chronic progressive non-communicable diseases making a huge demand on palliative care providers.[9]

Integration of palliative care with oncology enhances patient’s quality of life, decreases suffering and depression, ensures good end of life care, better patient satisfaction, and decreases cost by avoiding unnecessary chemotherapy or ventilatory support.[10-12] It helps in optimizing patients physical, mental, social, financial, nursing, practical, and spiritual needs of life.[13] Early integration of palliative care with patient centric approach decreases patient’s suffering and distress.[14] Palliative care can be incorporated at any point of patient’s journey through the cancer.[15]

VARIOUS TYPES OF PALLIATIVE MEDICINE DELIVERY MODELS GLOBALLY

Palliative medicine delivery models are of two types – hospital based and community based [Figure 1]. The hospital-based model can be inpatient, outpatient, mixed, or integrated. Comanagement hospital-based model has close integration with the critical and emergency teams as well.[16,17] Community- or home-based model can be provided by volunteers, nurses, or doctors.[18] It is provided at the patient’s home, hospice, nursing home, and other non-government organizations.[19] Sometimes, the home-based model is an integral part of the hospital-based model in which hospital doctors visit patients home to provide palliative care.[19]

- Types of palliative medicine delivery models.

Three types of models have been described for integration of palliative care in oncology.[20]

Solo practice model

Medical oncologists are solo practitioners and take care of all the patient’s issues.

Congress practice model

Oncologists take care of cancer diagnosis and management and refer them to other specialties for other concerns.

Integrated care model

Oncologists work in close association with multidisciplinary teams including palliative care team to provide comprehensive care.

PATIENT CENTRIC HOSPITAL-BASED INTEGRATED IRCH MODEL OF PALLIATIVE CARE

DR. BRA IRCH, AIIMS, New Delhi, is practicing hospital-based integrated palliative care model. Integrated palliative care model refers to integration of palliative care across all care settings to facilitate continuity of care, improve quality of life, holistic approach to care, sharing and allocation of coordination roles and responsibilities to improve service coordination, efficiency, and quality outcomes for patients and family carers. It provides consultation services referred from other departments for palliative services. It also admits those patients in need of inpatient palliative care for symptom management, any intervention, and for very distressed caregiver needing support. Palliative care at IRCH was started in 1983 with limited patients, facilities, and resources.

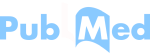

We have an integrated multidisciplinary teams that include pain and palliative physicians, anesthesiologist, medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiodiagnosis, intensive care services, social organizations, physiotherapists, pathologists, dietician, and other supportive teams [Figure 2]. Our main aim is to coordinate among various teams to set patient goals in accordance with patient needs and preferences.

- Integrated palliative care delivery system at IRCH.

GOALS OF AN INTEGRATED PALLIATIVE MEDICINE DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Stabilization of the primary disease by appropriate referral to the medical or radiation oncologists

Maximizing comfort and preparing for the possibility of progressive disease and future challenges

Facilitating transition of care

Enhancing compliance to treatment

To make informed decisions with less distress

To avoid unnecessary harmful therapy at the end of life

Decrease distress and improve quality of life of both the patient and their caregivers

Aid in advanced care planning.

The three main components of patient centric comprehensive care model practiced at our center are as follows:

Integration with various oncology and non-oncology departments of the hospital [Figure 2]

Spreading palliative care need and awareness to other departments through palliative programs and training

Integration of palliative care in the continuum of care in the primary healthcare system by creating awareness both among patients, doctors, and hospital administration

INTEGRATION WITH VARIOUS ONCOLOGY AND NON-ONCOLOGY DEPARTMENTS OF THE HOSPITAL

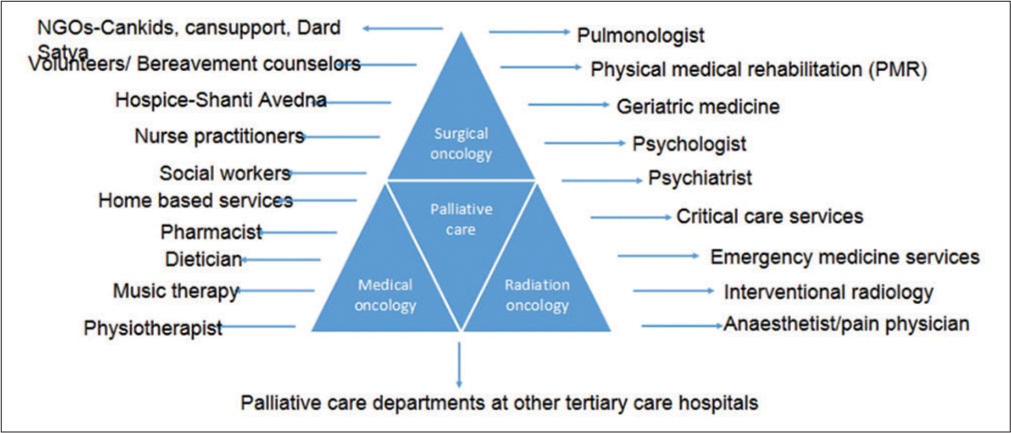

Patient centric comprehensive care model

Palliative care patients are at center of supportive care and they are consulted to other oncology and non-oncology departments from palliative ward itself [Figures 3 and 4].

- Patient centric comprehensive care model.

- Cancer assessment and management at IRCH.

Multidisciplinary tumor board

There is board room where faculties from multidisciplinary team will see one patient together and their goals and further plans are discussed.

SPREADING PALLIATIVE CARE NEED AND AWARENESS TO OTHER DEPARTMENTS THROUGH PALLIATIVE PROGRAMS AND TRAINING

Palliative care programs, research, and academic classes

A survey was done at our institute assessing awareness, interest, practices, and knowledge regarding palliative care among 186 medical professionals. It was found that 56% of respondents had not received any basic training in palliative care and poor program was identified as the most common barrier in learning palliative care.[21] About 77% of respondents had no idea about home-based palliative care services. However, knowledge of palliative care regarding opioid use, spirituality, euthanasia, and preparation for death was satisfactory among the participants.[21]

At our institute, 8-week certificate course in Essentials of Palliative care (CCEPC) is conducted twice a year in June and November month to train doctors and nurses in the basic concept of palliative care. Fifteen days observership in palliative care can also be done here. Regular conferences in palliative care are organized and multiple research activities are pursuing to provide benefits to the patients. We have regular academic classes 5 times a week including seminars, tutorials, audits, case presentation, and journal clubs. Pain-free policy has been started to make all the patients in any department free of pain.

Community awareness

October 13 is celebrated as World Hospice and Palliative Care Day every year in our department and patients and their families receiving palliative care are invited to share their experience and increase awareness regarding it. Besides this, public lecture, interaction with general population on FM radio or television and Cancer Treatment Centers Training programs in palliative care is done on regular basis.

Courses at IRCH

Various academic courses that have been started at IRCH are as follows:

3-year postgraduation in palliative medicine

3-year DM course in oncoanesthesia

PhD courses in palliative medicine

These new courses have improved awareness and research at our center.

Rotation postings of palliative medicine residents

Postgraduation in palliative medicine has been started 2 years back and three students are recruited every 6 monthly. Residents doing MD in palliative medicine have 1 month peripheral rotational posting in medical oncology, geriatric medicine, psychiatry, physical medicine, emergency medicine, pulmonary medicine, hospice, Cansupport, and Cankids to increase palliative awareness and learn palliative care in non-oncology patients as well.

Palliative care in an emergency unit

One palliative medicine resident is posted in an emergency department for palliative services, guidance regarding advance care planning, psychosocial support, and educating emergency room staff on managing symptoms.

INTEGRATION OF PALLIATIVE CARE IN THE CONTINUUM OF CARE IN THE PRIMARY HEALTH-CARE SYSTEM

Department of oncoanesthesia and palliative medicine delivers palliative care through an inpatient palliative care ward, outpatient pain, and palliative clinic and round the clock consultation team.

Two residents on the pager or follow-up duty treat patients with both acute and chronic pain admitted in any of the hospital wards. Every department has palliative pager number and they can call 24 h a day for pain or palliative referral. Telecommunication model of the continuum of care is practiced by providing 24 h of consultation to patients on phone as well. Every morning, there are compulsory rounds by the faculty on call and all the referrals are discussed. Around 60–70 patients with average seven patients on ventilator are seen monthly. Those in the requirement of acute inpatient or ICU services are transferred to the respective places.

ADVANTAGES OBSERVED WITH AN INTEGRATED PALLIATIVE MEDICINE DELIVERY SYSTEMS/SIMULTANEOUS CARE MODEL

Better management of physical, nursing, and psychosocial issues and thus better quality of life

Rapid consultation with other departments as it channelizes referrals to other departments

Saves OPD time of oncologist as they can refer to palliative care for psychosocial and spiritual counseling, decreases burden on oncologists

Better symptomatic management and family satisfaction

Decreases caregiver burden and fatigue

Patient preferences and goals are taken care of

Comorbidities can be optimized

Cater’s patients with both curative and non-curative intent, irrespective of prognosis

Decreased ICU shifting

Decreased hospital mortality as it encourages home death

Better follow-up of patients and better compliance to medications

Early pain control and early palliative care improves the outcomes of curative therapies and faith in the health system

Allows patients to live actively and independent with dignity

Avoids long waiting time for appointments to different specialties on different days

Patients are referred early and in more numbers. Early referral allows gradual transition of care[22]

Patients do not have to make choice between cancer treatments and palliative care. They can have access to both the expertise.[23]

SHORTCOMINGS OBSERVED WITH AN INTEGRATED PALLIATIVE CARE MODEL

Limited beds and thus limited admissions

Patient journey in the hospital in reaching palliative care is not smooth

Conflicts among medical professionals regarding the overlap of their role and responsibilities

Lack of trained staff

Lack of institutional guidelines with respect to palliative care.

BARRIERS TO AN INTEGRATED PALLIATIVE MEDICINE DELIVERY SYSTEMS

Delayed referral[24]

Stigma associated with palliative care

Collusion

Referral to palliative care depends on individual oncologist preference[25]

Lack of awareness and programs regarding palliative care among medical professionals and the general public

Requirement of additional appointment to palliative specialist

Lack of research and evidence

Lack of administrative and political support

Lack of palliative department at the tertiary care center

Lack of funding and infrastructure

Difficulty procuring opioids due to strict regulation on its prescription[26]

Competition from other specialties

Lack of medical insurance

Out of the hour services

Illiteracy, ignorance, and poverty.[27]

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR OVERCOMING BARRIER TO AN INTEGRATED PALLIATIVE MODEL

Electronic referral of all cancer patients to palliative clinic for early palliative registration and follow-up

Awareness of patient, caregivers, physician, and general population through training programs and media

Easy availability and access to opioids through easier government regulations and amendments

Good counseling and communication

Research and evidence supporting toward benefits of early palliative care[28,29]

Integration of palliative care in the continuum of health-care system at tertiary centers.

CONCLUSION

Palliative care avoids financial crisis and inappropriate hospital visits and hospitalization. An integrated palliative care model is the need of the hour in developing countries for making justice both to the patients and the resources available. It is genuine to start integrated palliative care department in all the cancer centers for providing holistic care to the patients. Patient centric comprehensive care model facilitates continuity of care, improves quality of life, holistic approach to care, and sharing and allocation of coordination roles and responsibilities. The growing awareness and evidence-based practice will reinforce medical professionals from other departments to refer their patients to palliative care early and timely. We hope that this model might help in creating patient centric comprehensive care model in various other cancer centers with limited resources.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Development of palliative care in India: An overview. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12:241-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research focus in palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:S8-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital; the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;115:119-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptom control problems in an Indian hospice. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23:287-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical use, misuse, and diversion of opioids in India. Lancet. 2001;358:139-43.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Models of delivering palliative and end-of-life care in India. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2013;7:216-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Quality of Death: Ranking end of Life Care across the World. Available from: http://www.graphics.eiu.com/upload/eb/qualityofdeath.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Columbia University 'Healthcare in India' Columbia University Continuing Education. 2011. Available from: http://www.ce.columbia.edu/fifiles/ce/pdf/actu/actu-india.pdf [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 19]

- [Google Scholar]

- 2021. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Available from: https://www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018 [Last accessed on 2021 Apr 15]

- [Google Scholar]

- Palliative care always. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27:13-6, 27-30, 32-4 passim

- [Google Scholar]

- Respite model of palliative care for advanced cancer in India: Development and evaluation of effectiveness. J Palliat Care Med. 2015;5:5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Definition of Palliative Care. 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en [Last accessed on 2011 Jan 07]

- [Google Scholar]

- A call for integrated and coordinated palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:S27-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Definition of Palliative Care. 2016. New York: Center to Advance Palliative Care; Available from: https://www.capc.org/about/palliative-care [Last accessed on 2016 Nov 11]

- [Google Scholar]

- The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2418-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delivery of community-based palliative care: Findings from a time and motion study. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:1120-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:23-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: Establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4013-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A survey of medical professionals in an apex tertiary care hospital to assess awareness, interest, practices, and knowledge in palliative care: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25:172-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of a half-day multidisciplinary symptom control and palliative care outpatient clinic in a comprehensive cancer center on recommendations, symptom intensity, and patient satisfaction: A retrospective descriptive study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:481-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antineoplastic therapy use in patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit at a comprehensive cancer center: A simultaneous care model. Cancer. 2010;116:2036-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Late referrals to palliative care units in Japan: Nationwide follow-up survey and effects of palliative care team involvement after the Cancer Control Act. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:191-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A population-based study of age inequalities in access to palliative care among cancer patients. Med Care. 2008;46:1203-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the Endof-Life. 2014. Available from: http://www.thewpca.org/resources/global-atlas-ofpalliative-care [Last accessed on 2016 Aug 24]

- [Google Scholar]

- Current status of palliative care--clinical implementation, education, and research. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:327-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:20-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]